Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala

Some trips are well researched and planned ahead of time.

Other times, you’re standing on a Panajachel dock gazing out at a beautiful Guatemalan Lago Atitlán wondering how to fill your afternoon with the few Quetzales you still have in your pocket. You might pull out your phone and google “which town, lake Atitlan?,” and if you stumble across a certain travel blog, you just end up in the tiny town of Santiago.

The boat from Panajachel to Santiago costs 25 Quetzales – about $3.50 – and it leaves whenever it is full. “Maybe 30 minutes?” says the man at the dock; we were sure to be back in 15, adding 50.Q to the fat stack of cash in his hand before settling into a motorboat that leaves when it is packed to way more than “capacity.”

Guatemala as a whole is more than 40% pure indigenous (mostly Mayan), but Santiago leans heavily toward the indigenous side with many people speaking barely enough Spanish to sell the typical Guatemalan souvenirs to the few tourists like us that choose it over the seven other towns surrounding Lake Atitlán. The only English words anyone seems to know are “cashew” and “shoe shine.”

A couple hundred meters uphill past the dock and we’re into the town – a dystopian mass of concrete, rebar and razor wire. It looks as if people started building a town at one point – maybe twenty years ago – then just stopped in the middle of the project.

Already in a bit of a hurry – we can see storm clouds coming in – we accept the offer of a tuk tuk driver and tell him we want to see the house of Maximón. He tells us he can take us to see the house for 10.Q.

The driver leads us to his house and tells us to wait outside while he pulls the tuk tuk around. He offers to take us to five beautiful sites for 50.Q. It’s a tempting offer, but we’re in a bit of a rush to get back to Panajachel before dark, so we tell him that we just want to see the house. He agrees and before we know it, we’re climbing into the tiny three-wheeled death-trap and speeding off through the narrow streets of the eerie, almost uninhabited concrete jungle.

After a few minutes, he stops in front of a narrow ally and points – just go that way a little ways, it’ll be on the left, for 30.Q he’ll wait for us and tell us stories. Deciding against the offer, we hop out and, as he speeds away, we nervously look back to the ally that he had pointed to. I’m not sure what we were expecting, but it certainly wasn’t this. It’s times like these when you start remembering all of the Central American horror stories you’ve heard. Oh well, we’ve come this far.

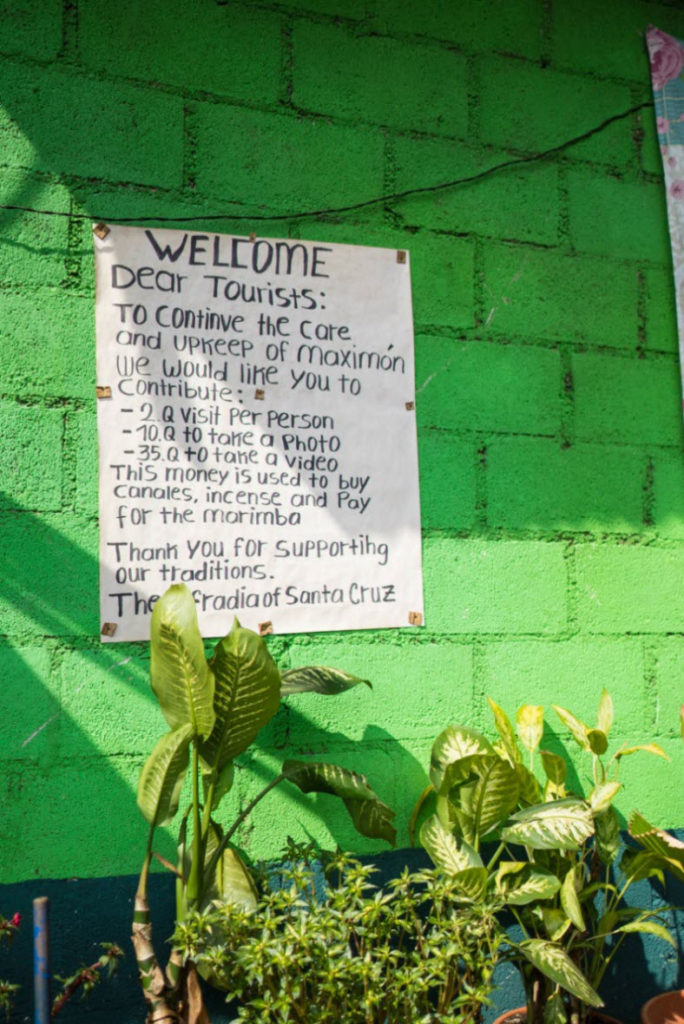

We start down the ally and – true to his word – after passing three or four, umm, residences, we see a large green wall with a hand-written sign for the tourists like us that have come to see Maximón.

It’s 2.Q to see the effigy of the cult saint, 10.Q if you want to take pictures. I discretely pull 12.Q out of my pocket and we start into the house.

The house itself is a simple one-room building with Maximón’s well-dressed effigy sitting right in the doorway next to one of his attendants. Surrounding him on all sides are decorations, other wooden statues of Christ and other saints – each better dressed than the last. The room is dark, lit only by candle sticks melting on the concrete floor and twinkling Christmas lights around the statues and the large glass coffin with the 3/4 sized wooden corpse of Jesus Christ.

The attendant grunts and we hand him our money – he moves to immediately pin my 10.Q photography fee under Maximón’s scarf. I immediately drop to one knee to take a picture of the statue and the attendant seems unfazed – as are they as we meander around the small, smoky room taking pictures of everything.

The attendants seemed actively uninterested in talking to us, and having sent the tuk tuk driver on his way, We have only Wikipedia to help us understand the small room we were standing in.

Maximón (pronounced /mæʃiˈmoʊn/ or /ˈmɒn/), also called San Simón, is a folk saint venerated in various forms by Maya people of several towns in the highlands of Western Guatemala. The veneration of Maximón is not approved by the Roman Catholic Church.

The origins of his cult are not very well understood by outsiders to the different Mayan religions, but Maximón is believed to be a form of the pre-Columbian Maya god Mam, blended with influences from Spanish Catholicism. It has been suggested that the name Maximón is a combination of Simón and Max, the Mam word for tobacco.

The legend has it that one day while the village men were off working in the fields, Maximón slept with all of their wives. When they returned, they became so enraged they cut off his arms and legs (this is why most effigies of Maximón are short, often without arms). Following this, he somehow became a god, or perhaps prior to this he had been possessed by the god. Later, with the introduction of Christianity, Maximón’s effigy was replaced by one of Judas Iscariot in Holy Week carnival rituals.

Where Maximón is venerated, he is represented by an effigy which resides in a different house each year, being moved in a procession during Holy Week. During the rest of the year, devotees visit Maximón in his chosen residence, where his shrine is usually attended by two people from the representing Cofradia who keep the shrine in order and pass offerings from visitors to the effigy. Worshipers offer money, spirits and cigarsor cigarettes to gain his favor in exchange for good health, good crops, and marriage counseling, amongst other favors. The effigy invariably has a lit cigarette or cigar in its mouth, and in some places, it will have a hole in its mouth to allow the attendants to give it spirits to drink.

The worship of Maximón treats him not so much as a benevolent deity but rather as a bully whom one does not want to anger. He is also known to be a link between Xibalbá The Underworld and Bitol heart of heaven (Corazón del Cielo). His expensive tastes in alcohol and cigarettes indicate that he is a sinful human character, very different from the ascetic ideals of Christian sainthood. Devotees believe that prayers for revenge, or success at the expense of others, are likely to be granted by Maximón.

Maybe the impressive amount of beer bottles in his house are a tribute to the virtues Maximón has instilled in his attendants?

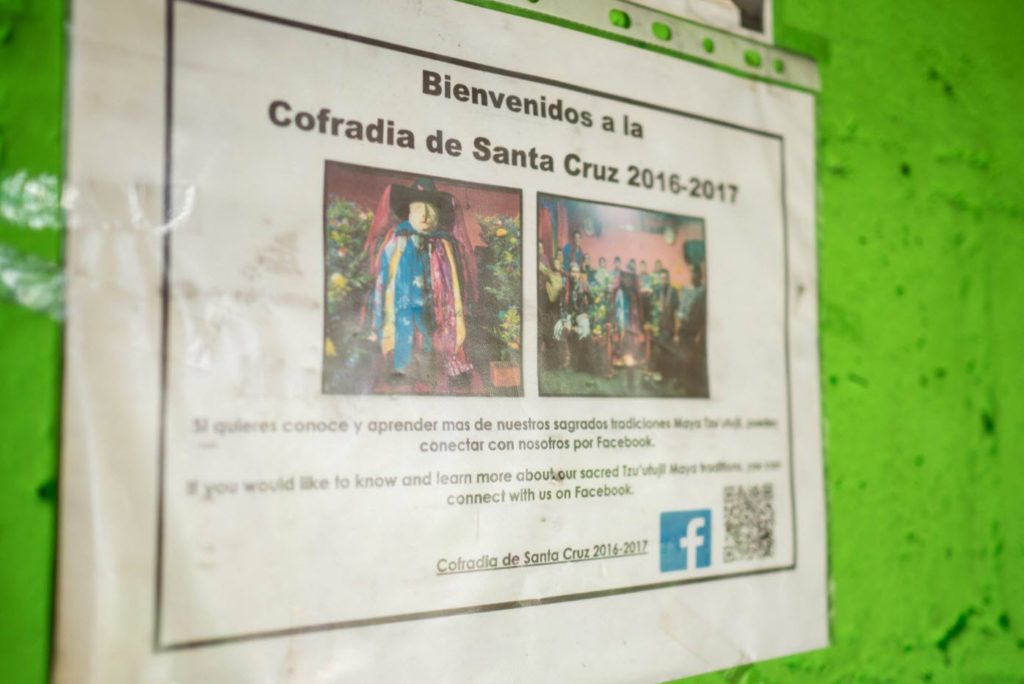

In a beautiful nod to inter-temporal culture, this Mayan-god-turned-pseudo-catholic-saint has a facebook page kept up by his Cofradia. It hosts videos of his procession this past year.

As we turn to leave, I attempt to discretely snap a few pictures of some attendants re-dressing one of the wooden statues – they’re not subtle in their disapproval.

We leave with some half-hearted good-byes and head back through the town on foot to the dock where we’re lucky to grab the last two empty seats on a boat heading back to Panajachel.