Ch. 2: How did design stop being a verb and start being an industry?

Despite paying lip-service (and selling a lot of books) to make “Design” more accessible, it is amazing to me how exclusive this world is. Design tools are highly complex and priced to inaccessible levels. Design conferences are expensive and conjure up stereotypes of aloof hipsters that use big words to describe simple phenomena. Design degrees are expensive.

When I say “design,” I mean specifically the cottage industry of people that call themselves “designer.” It used to consist mostly of people engaged in graphic, industrial, or user interface design, but as concepts like “Design Thinking” and “Human Centered Design” entered the business world in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, this industry began to grow and expand its scope.

The core of this may involve the shape that “thought leaders” in the Design industry give to the craft. Speaking about Design as a discrete process handled by experts makes sense to us((I used to work for one of the big companies)) – and many feel that the enemy of good design is when our process gets diluted by outsiders. In the past half century or so, we in the first-world west have tried our hardest to make the term “design” conjure up imagery of post-it note covered walls and a magical Stanford/HBR/IDEO supported vision of an elusive business strategy (or whatever) in the minds of middle and upper managers.

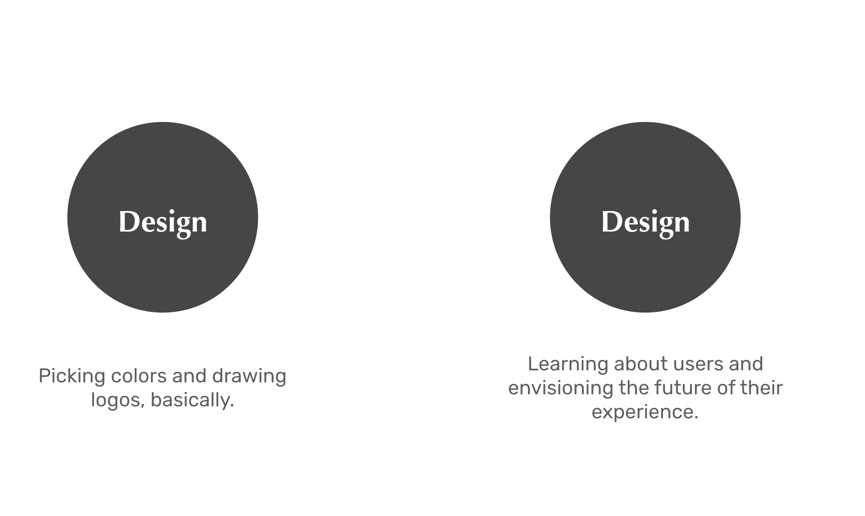

This has created essentially two meanings of design in modern vernacular. In the first-world west, Design has become some kind of magical unicorn where people learn about users and then draw pretty things on post-it note covered walls. In the rest of the world, it still means picking colors and drawing logos.

Both of these definitions have their value, but we must recognize them as different. They seem to have emerged and solidified sometime in the later half of the 20th century as the idea of design was penetrated by a neoliberal business world and worldview.

“Design Thinking might have a “buzzword” connotation to it in these first decades of the 21st century, but if we look back to some of the most influential writers about “design” during an earlier period, we’d notice that they tended to use “design” in a third way – a way that meant simply “planning.” Many of them didn’t have the title of “designer” – they were engineers.

The “design” they were interested in wasn’t a “role,” it was a process: the planning phase of the thing that an organization was going to create. They were interested in how these things came to being – how did humans go from nothing to something? What was the process?

The “design” they were interested in wasn’t a “role,” it was a process: the planning phase of the thing that an organization was going to create. They were interested in how these things came to being – how did humans go from nothing to something? What was the process?

Those who studied design thinking did find a lot of interesting and useful things that humans did while engaged in the design phase of an endeavor which they wrote about in an increasingly larger canon of work that was appreciated and, eventually, commercialized by the growing design industry.

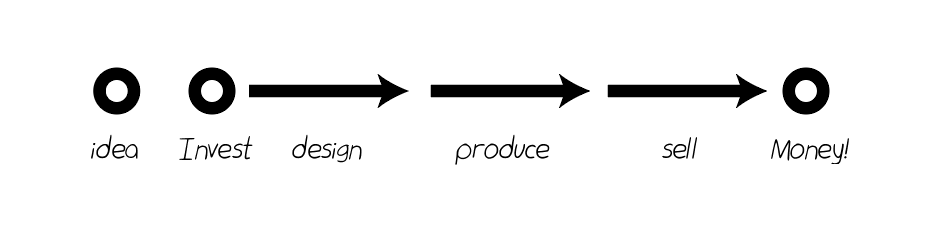

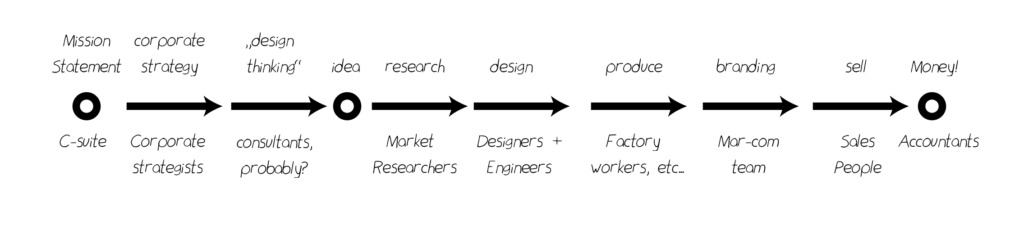

In the corporation of the 20th century, the distinction between a “role” and a “process” didn’t matter a great deal. The paradigm was the Smithian pin factory((Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776. Widely regarded as the bible for the corporate elite in the west don’t actually read, but reference as often as possible. It is important for the context of this essay, therefore that we simplify and slightly misunderstand it as well.)) wherein the division of labor was largely separated by function and these functions were arranged linearly from idea to money.

“Design” wasn’t originally a “role,” it was a process: the planning phase of the thing that an organization was going to create.

Most importantly, this process could be stretched over timelines that mostly could support Wall Street projections for investments of large sums of money in things and expected returns from big wins((This is actually the same model that many silicon valley startups had in the 2010’s or the Chinese tech scene of today – see an idea, raise capital, sink money, try to win big. In winner-take-all markets like social media, this makes a lot of sense – having big war chest means you can out-bleed your competition. In non-winner take all markets, it becomes a bit more difficult to justify huge investments in early-stage companies, an ideas like “bootstrapping” and the “lean startup” practices developed.)).

The problems, of course, was that there was a huge amount of uncertainty with this process. What if ideas were bad? Wouldn’t it be best if we had some ways to make sure that ideas were good before we sunk fat stacks of cash into them?

The process evolved,

Software developers call this a “waterfall” process. Each step in the linear chain must happen before the preceding step, but the steps themselves are largely independent. The cool, and clean, thing about this model is that you can identify certain humans for each part in the chain.

Fill in the slots with the “best people” and you’re good((Well, hire the best “HR” people so they can find the rest of the “best people,” then you’re good.)). In a waterfall process, your part of the process is synonymous with your role, so it doesn’t matter if different roles have different ways of interpreting information. Your peers are likely to have a similar background, and you can specify that deliverables to your phase are structured in a certain way (and then grumble with your peers about how the people in the chain before and after you don’t understand your perspective).

Fill in the slots with the “best people” and you’re good((Well, hire the best “HR” people so they can find the rest of the “best people,” then you’re good.)). In a waterfall process, your part of the process is synonymous with your role, so it doesn’t matter if different roles have different ways of interpreting information. Your peers are likely to have a similar background, and you can specify that deliverables to your phase are structured in a certain way (and then grumble with your peers about how the people in the chain before and after you don’t understand your perspective).

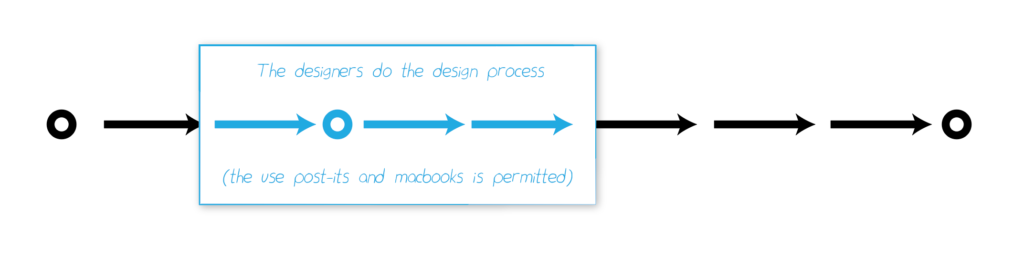

In this world, our team would inherit a directive from the strategy, then we would go through “the design process” as a “design team,” then we would deliver those designs to the engineers for production.

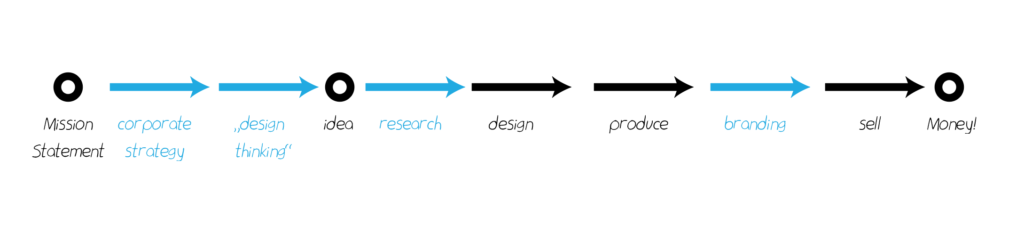

This structure creates risk because the assigning of “roles” and “departments” creates barriers to the natural flow of information, and wherever these barriers are created, eddies will naturally arise. As “design” has worked its way up the value chain, it has taken on ever-more strategic roles. As Design Thinking becomes more popular, “Designers” are brought in to make more strategic decisions for the organization. The advent and popularizing of “Design Research” as a practice has positioned Design as an information gathering mechanism, and the traditional role of Design – to craft artifacts that facilitate planning – means that it also has leverage over determining what a company brings to market.

This structure creates risk because the assigning of “roles” and “departments” creates barriers to the natural flow of information, and wherever these barriers are created, eddies will naturally arise. As “design” has worked its way up the value chain, it has taken on ever-more strategic roles. As Design Thinking becomes more popular, “Designers” are brought in to make more strategic decisions for the organization. The advent and popularizing of “Design Research” as a practice has positioned Design as an information gathering mechanism, and the traditional role of Design – to craft artifacts that facilitate planning – means that it also has leverage over determining what a company brings to market.

The compartmentalization of these processes creates an interesting dynamic where an organization attempts to focus it’s learning and strategy to one section. The obvious disadvantage is that it puts a lot of leverage into one part of the system that may or may not be qualified to make ever more impactful decisions. Because design has traditionally been far from the point of value delivery (remember, we still have to go through several more steps before getting to “The World”), Design is typically insulated from real world learnings.

However, compartmentalization has another factor that taps one of the most common systems-thinking problems discussed.

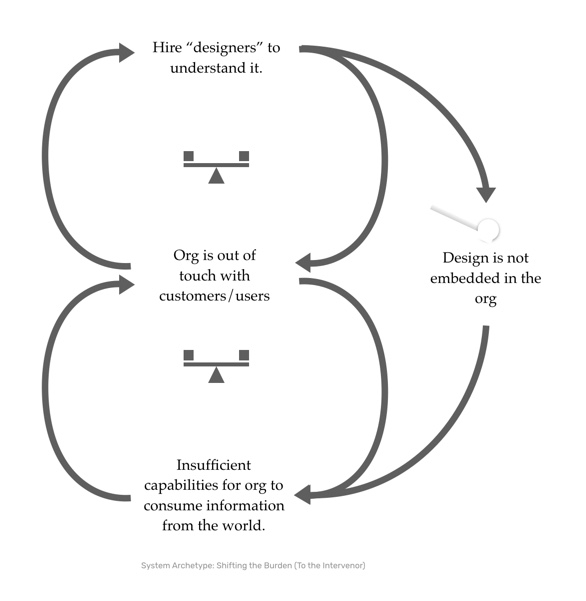

Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor

Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor

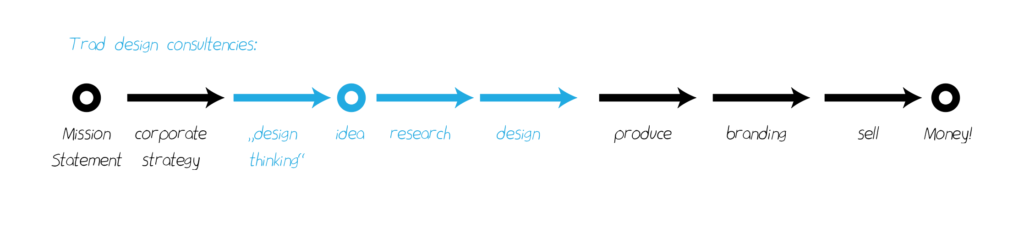

Sometimes staffing this is tough, arguably, by “hiring designers (noun)” rather than teaching the organization “to design(verb),” the industry creates a scarcity market for individuals with certain hard-skills. When “design” is in vogue, these individuals can be hard to source, but if you can’t get the right humans, you can supplement with consultants. With a modular model like this, inserting consultants is easy. Every type of consultant has her notch, but design consultancies traditionally played here too:

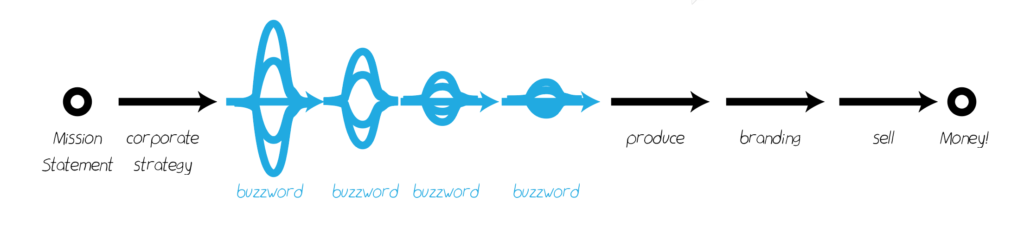

… but their version of the diagram would look more like this:

Over time, the IDEOs, frogs, Continuums, and others in the design consulting world started working their way up the chain toward corporate strategy. Others worked their way down the chain toward production and branding.

Over time, the IDEOs, frogs, Continuums, and others in the design consulting world started working their way up the chain toward corporate strategy. Others worked their way down the chain toward production and branding.

Systems thinkers call this “shifting the burden to the intervenor” because rather than dealing with the structural problem at play (the fact that the organization is out of touch with those that it is supposed to be co-creating value with) it opts for the short-term solution of outsourcing the design process((at least, the “human centered” part of the design process. Some companies also outsource their technical design which creates an organization that operates more as a federation than a unified entity. While this has its advantages, it comes at the cost of information fluidity)). Needless to say, compartmentalizing “design” erects enough barriers to information flow – placing the process outside the organization runs the risk of making these barriers insurmountable.

This leads to the natural conclusion of “shifting the burden to the intervenor” problems: the organization becomes addicted to intervenors. In particular, it means the design team – whether internal or external – is increasingly relied on as the source of understanding the user. This has the potential to isolate the team.

A Problem Growing in Cost

A Problem Growing in Cost

For the most part, though, everything was cool with the linear organizational process because the process was cleanly defined and the timelines were long. Everything was modular, and a company could decide to bring this part in-house or outsource that part based on its DNA, of its culture, the opinions of it’s board, and whatever their buddies in the management consulting firm told them to do((Between 2015 and 2020, we started seeing massive buy-ups of design firms as “design” started to be seen as a core competency that might be a competitive advantage, so best to have that in-house (if you’re a producer) or on staff (if you’re a management consultancy).)).

This model worked well during the 20th century when demand cycles were long and transactions costs were high because the main challenge of business was managing the “detail complexity” of systems operating at scale that that changed slowly.

There are two problems, however, with this model. The first problem is that it doesn’t really work all that well for the faster-moving problems of the late 20th and early 21st century. As Senge noted in the 90’s,

sophisticated tools of forecasting and business analysis, as well as elegant strategic plans, usually fail to produce dramatic breakthroughs in managing a business. They are all designed to handle the sort of complexity in which there are many variables: detail complexity. But there is a second type of complexity. The second type is dynamic complexity, situations where cause and effect are subtle, and where the effects over time of interventions are not obvious. Conventional forecasting, planning, and analysis methods are not equipped to deal with dynamic complexity.

The second problem is that when it comes to measuring results, ‘Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space’ ((Systems thinking Law #7), but by the time the measurements have occurred, the consultants((and, with today’s millennial workers, probably half of your in-house staff are already gone)).

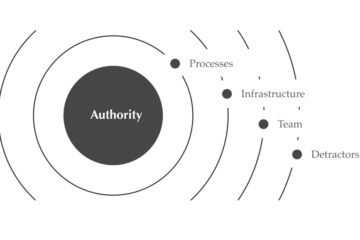

Now, I know this all sounds arcane and a bit facetious to some readers, but this is exactly the workflow that most companies continue to encourage. Few managers would say that they want to be a part of this system, but even the most forward-thinking managers often find themselves trapped. This is a structural problem – everything from the way we track accountability , annual board meeting cycles(processes), to the tools we use and budget structures (infrastructure), titles that we hire for (population), and behaviors we discipline (“agents”) make such a process nearly impossible to break out of.

If your middle-manager fails to produce, you can fire her, but it bears repeating that, “placed in the same system, people, however different, tend to produce similar results.”

The “design industry” did not create this problem – however, it is an industry that profits immensely from “intervening” and creating the impression that what we do is somehow something special that can’t be replicated by non-”designers.” By calling ourselves designers, we imply that others are not. By using inaccessible tools, we push others out of the process. By using jargon-sounding buzzwords to describe our processes, we discourage others from participating.

And by perpetuating the idea that understanding humans and crafting experiences for them is a unique skill, we reinforce a cancer that the system has created. When we cling onto it, we secure an immediate windfall at the expense of killing our host.

Unfortunately for designers, the design industry has far from a monopoly on “innovation.”