Organization design is tricky. Most organizations don’t even think about it – in pursuit of our day to day goals and tasks, a system simply emerges. We don’t often give organization design a lot of thought until we see a simple change we want to make and are baffled by how difficult it is for the change to take hold.

Much ink is spilled about systems thinking and how we can use it to better think about organizations. While conceptually, writers like Peter Senge can give us an understanding of the philosophy – these big ideas can fall flat when we try to share this style of thinking with others in our own organizations.1 What do we do, however, when we want to help people get a general understanding of the leverage points in a system?

One of the most useful model I’ve found in recent years for understanding and describing the distribution of power between nodes in a system is John A. Warden’s “Five Rings” model from his book Winning in Fast Time. As I’ve used the model to understand and explain systems concepts I’ve adapted some of the wording to be more congruent with the collaborative work philosophy that I advocate. In this short piece, I:

- Briefly describe Warden’s “5 Rings” model

- Outline the changes I’ve made in the model that I use throughout my other writing.

The Organization of the Parts

Herbert Simon tells us in that “we do not have to know, or guess at, all the internal structure of the system but only that part of it that is crucial to the abstraction.” In most cases, “the aspects in which we are interested arise out of the organization of the parts, independently of all but a few properties of the individual components.”2

This holds true for human organizations – the character of an organization (and the character of its leverage points) has more to do with the structure of the system than the personalities of the individuals that make it up. In the Fifth Discipline, Senge tells us that the reason “…structural explanations are so important is that only they address the underlying causes of behavior at a level at which patterns of behavior can be changed. Structure produces behavior, and changing underlying structures can produce different patterns of behavior.” This structure, however, is not external to the nodes of the system – it is made up of them, the power and structure of the system itself is distributed through them.

In traditional hierarchical systems, almost everything was delegated from the top of a hierarchy, so understanding the distribution of power through an organization wasn’t much of an issue. Modern systems, however, and the nature of modern knowledge work means that these systems are less visible. Adding more nuance to the fractal nature of nodes gives us the visibility we need to find the leverage points in ever more complex organizations.

To do this, we must use a more nuanced model to map influence in the system. A single node (for instance, a human or a department) may have immense leverage over certain actions the system takes and no leverage over other actions. For this reason, it is generally impossible to have a static systems model.

The anti-fragility of a system also requires a more nuanced understanding of relationships between nodes. In particular, processes and infrastructure exert such leverage over human individuals that it is critical for an organization to map, understand and shape their influence. This is only possible, however, if we’re able to first add these “process” and “infrastructure” lenses to our models.

What is the Five Rings Model?

The “Five Rings” modes was developed by John A. Warden, a military strategist that specialized in air-combat strategy. Warden was specifically interested in systems change – a difficult task considering that “when you push on a system, the system pushed back”3.

John A. Warden’s Winning in Fast Time consists of management strategies based on systems thinking.

That “push-back” tells us something about what makes a system strong – the nodes within a system are dynamic and opinionated. Pushing on a system disturbs the equilibrium, usually in a way that is not appreciated by the nodes. Nodes, therefore, tend to over-correct in the area where change is threatened. We can see this in as diverse situations as the toughness of scar tissue or the tendency for more terrorists to emerge after military forces attack them.

Warden argues that the only way to overcome this is to “shock” the system – a system must be completely paralyzed to disable its ability to “push back.” In Winning in Fast Time, Warden outlines the theory to do this.

Critical to the success of this theory is understanding how the system works in the first place. To shock the system we must locate and map the system’s “Centers of Gravity” – the areas in the system that exert the most leverage. To find these centers of gravity, we have to understand five basic forces that operate within the system – both within the system as a whole, and within each of the nodes that make up the system.

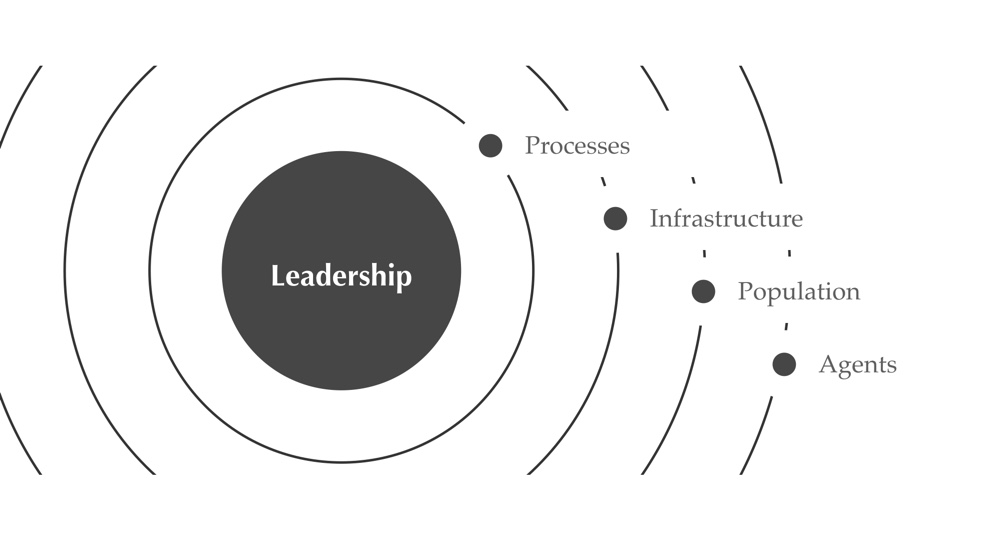

These five forces within the system exert different amounts of leverage within the system. Warden visualizes them as “Five Rings,” with the inner ring exerting the most leverage, and the outer ring exerting the least.

The rings (quoting heavily from Warden’s book) are as follows:

LEADERSHIP

Components that set direction for the system and help it respond to changes in its external and internal environments.

Warden notes that “The Leadership ring of a business organization contains the individuals (or in some cases the hierarchical units) that give direction to a company… Chief Executive Officer and Chief Operating Officer will fall in this category, but it would be a major error to include only the officially designated company leaders. We would expect to see included in this ring some informal leaders and some major influencers who are not even in the company… The Leadership ring of a market system contains the organizations and individuals that give direction to the market.”

The most important aspect of this ring is that it gives direction to the nodes it has power over. This direction may be either overt (explicitly telling the “population” what to do), or through the manipulation of the processes and infrastructure of the system.

PROCESSES

Components that convert energy within the system and enable the components of the system to interact. In biology, this may be photosynthesis. In an organization, it can be anything from the way expense reports are tracked to the way people argue in a meeting. Humans are creatures of habit, and processes emerge out of the collective (often tacit) agreement of a social organization, so individuals rarely have any leverage over them.4

INFRASTRUCTURE

Components that hold the system together.

The Infrastructure ring for an organization and a market includes things that bind the entity together—physical things like computer networks and telephone systems, as well as nonphysical elements such as hierarchy rules, business models, and protocols.

POPULATION

Components that can be classified by function.

“The Population ring within an organization contains the groupings—the demographics—of its people. These are not specific people, but are categories of people who have enough similarity that you can communicate with them and affect them to some extent as a group.”

AGENTS

Components that actively promote and defend the system. They give the power to sustain, advance, and protect the system. “Because agents do not make policy, components in the Agents ring should not command too much of our attention… Concentrating efforts on the fifth ring— the place where “tactics” are most concentrated—rarely has significant or sustained payoff without a substantial cost.”

We need to be careful about agents, though. Agents are only irrelevant if they have no formal or informal authority – if they have authority to affect processes or infrastructure, they should actually be classified in the Leadership ring.

The balancing act.

System design is a balancing act. A more centralized system can quickly and forcefully mobilize, but is brittle. As strategists like Warden are quick to point out – by simply neutralizing a hierarchical system’s leadership, the system will fall apart – systems get their robustness from their distribution of their centers of gravity. All real systems (whether it is explicitly stated or not) actually have multiple centers of gravity that must be neutralized for the system to actually fall apart. Systems that distribute more power horizontally to the nodes are more robust, but more difficult to mobilize.

Most modern work environments champion egalitarian style notions, some even going so far as to champion “democratic” values. While most of this seems surface level, including simple HR perks like parental leave, lax dress code policies, or football tables with free lunch, some practices such as agile software development or “intrapreneurship” systems actually seek to push autonomy down to the nodes of the system.

There is a tremendous amount of research to support the idea that systems in general – and knowledge work in particular – may benefit from more horizontal structures. If this is true, how do we square this with the idea of “leadership” as a central node? Does it even make sense to have it there?

I argue yes.

Why do we need the central ring?

Leadership is like design – when it is good, it is hard to notice, but we all notice when it’s bad. Personally, I believe that less hierarchical systems are the way of the future. However, when we model systems the central ring remains important for three reasons:

- All human systems have leadership, and we need our models to be descriptive5

- Process are powerful and coercive, someone has to take charge of them.

- It is important to have unifying factors – even if tacit and symbolic

I will argue each of these in turn, but before I do, I believe a semantic change is useful. “Leader” sounds like a human agent – a person or group of humans that sit at the top of a hierarchy. While this is undoubtedly the most typical expression of a central node within a nationstate or an organization, I do not believe it fits our purposes.

In my modeling, I use the word “Authority.” This word in everyday English makes the model feel more comfortable ad different fractal positions and more concisely articulates the role that this ring plays in contextual situations. In the following sections, I describe both why this ring is necessary and why the term “Authority” better describes its function.

Descriptive models.

The first and most obvious reason that we want to include this reason is that it behooves us to create models that are descriptive rather than prescriptive.

All human systems naturally have leaders. Period. There are no counter examples – even what few anarchic systems have been tried over the years have always had individuals that had influence over the system. Changing a map does not change the landscape, and lying on a map will cause people to crash.

However, “Leadership” sometimes connotes a formal role rather than simply a functional one. At times, this can misdirect our attention.6 Because we want to map descriptive systems, it is more useful to call this ring “authority” – functionally we use this ring to denote the agent that has the authority to give direction. More importantly, the center ring has the authority to mandate process and infrastructure changes.

Coercive Processes.

Deming pointed out in 1993 that “A manager of people needs to understand that all people are different. This is not ranking people. He needs to understand that the performance of anyone is governed largely by the system that he works in, the responsibility of management.” In other words, a bad system will defeat a good person every time.

A Leader is the one that has the authority to change processes.

Otto Scharmer echos this when he reminds us in Leading from the Emergent Future that in general, when you replace a person within the system, it is more likely that the person will change but the system will not. Some of this leverage over the individual is contained within the “population,” but much more of it is contained within the dual layers of processes and infrastructure. This is why “Population” is placed in an outer ring, but Processes are close to the center – an individual in the population ring cannot sustain a long-term resistance against a process.

What, then is a “Leader?” A Leader is the one that has the authority to change processes. Authority, again, is key. To the extend that “democracy” does exist, its raison d’entre is to change the processes and infrastructure that bound individuals in a population.

Interestingly, even within democratic or egalitarian situations, individual population members do not have carte blanche to change processes or infrastructure. Why? Processes and Infrastructure affect – and, thus, contain – the actions of individuals within the population. To allow anyone to change them on a whim would tip the balance of the delicate infrastructure that enables humans to work together and the whole enterprise would fall into chaos. Process and Infrastructure change, therefore, must only be taken with care and executed absolutely.

Traditionally, this authority was given to a wise leader, This worked within simple repeated systems, or in systems where an individual is able to make system monitoring her specific task. In the modern era, it is more common for teams to designate time for “retrospectives” and to use certain democratic practices for experimenting with process of infrastructure change. This works because the system is time-bound and predictable to the population.

Symbolic Leadership is Important.

I do not think that it is a coincidence that in the era where formal directorial leadership is failing, there is a rise in demand for company “values” and other propagandistic paraphernalia.

There are two ways to create alignment within an organization. The first is to centralize authority and have an individual, charismatic leader direct the minions. This works well for simple situations or situations in time-bound situations (generally situations of crisis).

However, as a fore mentioned, this method both makes the organization brittle and places a limit on the amount of knowledge the organization can consume and execute on.

Contemporary systems delegate decision-making authority downward and increasingly rely on rhetorical methods like mission statements for strategic alignment and values statements for cultural continuity.

For this reason, I argue that both of these are authority centers that can be found in the organization. Many organizations have hero stories or actual heroes that set the tone for the organization – often these derive from the CEO or Founder herself, and manifest in internal propaganda such as videos that are internally or externally facing. These systems are more difficult to seed and control, but also provide a strategic advantage for the organization as it does not need to centralize (and, thus bottleneck) its decision making.

Still, this is an uncomfortable shift for the conservatives among us – it is just as likely to create a “hacker” culture as a “misogynist” culture – some of these are less desirable than others. Likewise, it trends toward homogeneity.

At times, these practices go too far and rogue population members differ to higher authorities. For example, in a culture that trends toward discrimination, an internal agent may appeal to a government authority to impose sanctions on the organization, thus prompting leadership to take a more traditional approach by centralizing hiring authority using more traditional means.

These are extreme cases, however. For the most part, charismatic informal leaders within a group will set the tone and a moral authority will emerge. Two examples should illustrate this point.

Though I used to work in a place that officially supported “work-life balance,” the informal leaders of the organization worked long hours and nurtured an obsession with their jobs. Whether they were sanctioned “leaders” was irrelevant – they held enough sociological weight and commanded enough emotional energy to set the tone for and create symbolic in-group indicators within the organization.

The same organization also had no official political affiliations, but it was obvious that those that held both formal and informal power favored a certain political leaning. For anyone to express an alternative political opinion around the water cooler would have signaled a moral violation – one that may derail your career or maybe even get you let go. Though there were not official polices about this, the informal, symbolic leadership held sway by establishing norms and – therefore – creating the opportunity for people to be identified as deviants.

Name Changes

Warden is a military strategist and – while his framework can be applied to all systems – the naming he uses makes the most sense if you’re planning to stun an enemy system with an air attack. Since most of my own writing is about human systems in various organizations, I’ve opted to use less confusing names. The most important is changing the “Leadership” ring to the “Authority” ring, but I’ve made a few other changes to the Five Rings model which specifically help discuss teams within organizations. These changes admittedly trade the model’s fractal scalability for clarity – but since trying to describe “agents” and “populations” to people in meetings is so difficult, the trade is worth it most of the time.

Authority (from Leadership)

Whether we believe that the above mentioned cases are just or unjust is irrelevant. As discussed in the first point – “leadership” is a natural occurrence in human systems, and thus any descriptive map should show them. Since they describe systems of formal and informal authority, however, I choose to change the name in my own representations.

Team

I’ve also chosen to use the word “team” instead of “population” in specific contexts because it just sounds nicer. Particularly in self-organizing teams, it is important to discuss with the team the effects that processes and infrastructure tend to have over us. Through cultivating this awareness, we can have productive discussions about how to change our processes and infrastructure. In some situations, these changes can be made by the team, in other situations, they need to petition management for a change. In either case, it makes no sense to pretend that the team has more leverage than it does.

Detractors

While the term “Agent,” is fun, most people find it confusing. More importantly, it hinders conversations because in English “Agent” tends to mean any individual with “agency” to act. In our system it is often useful to refer to an Authority figure, population member, and (retracing) “agent” as all agents. Since the functional role of Warden’s “Agent” is to detract, I’ve called them “Detractors.”

Using this model in Everyday Life

With these changes, I have found this model useful for understanding everyday life – particularly life and behaviors within organizations. For a manager, it helps focus one’s time by enabling us to prioritize high-leverage opportunities (usually processes) and ignore low-leverage things (like detractors – with the exception of people that act like detractors but are actually informal authority figures).

This model is also a great way to help a team break-down and examine its processes and infrastructure. Human individuals within organizations traditionally have very little power day to day to change move the levers of productivity – but it is rare for us to stop and think about why. This model gives both an answer to that question, and a starting point to craft strategies for high leverage change.