The effect of neoliberal values on late 20th century design practice.

To make the case that late 20th and early 21st century design rested on the same values as neoliberal economic and political policy, we must see whether there is a commonality in practice and theory between these two as contemporary movements.

For a shift in design practice to coincide with the rise and decline of neoliberalism, we would expect to see initial ideas to seed in the industry in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s and develop toward an apex between the late 1980’s and early 2000’s. We would then expect to start to see the initial seeds of around the time of this writing, the early decades of the 21st century (which I explore in greater detail in Part II).

If neoliberalism and modern design theory do, in fact, share values, we can expect to see certain shifts in the way “design” is discussed and practiced over the course of this time period. We would expect to find the energetic desire for a universal aesthetic of the early 20th century replaced with an emphasis on individuals in contextual situations. Specifically, we would see the industry responding to the re-orientation of agency and value around the individual with some specific responses to:

Distributed, Contextual Information

The industry shifting toward new methods of collecting and consuming information in these contexts.

Emergent Order: A belief in the Invisible Hand

This industry of “planners” aligning around the new nuclei of power and value: individual consumers.

Governance through Principles, not plans

An industry evolving toward establishing general rules of practice rather than standard solutions to problems.

In essence, we would expect to see a shift from design being a high-minded, normative practice toward a practice that studies, celebrates, and seeks to articulate the micro interactions of individuals in context and puts the ideals of individual choice and agency at the heart of its practice. This design would seek to serve the whims of the individual rather than shape them.

Before analyzing the effects on the study, process, measures of “quality,” and who is looked to for measuring the quality of design, it is helpful to summarize some key trends in the design industry of the 21st century.

The evolution of design in the late 20th century

The modernist era was driven by the normative application of universal aesthetics consistent with a simplistic understanding of the relationship between scientific (thought of largely through mathematical) rationality. Just as an engineer could master the laws of nature to create ever more complex machines, the designer could master aesthetic principles and, in her studio, apply them to commercial objects.

A shift, however, was inevitable. In the United States, a focus on more free-market capital led to a rise in the corporation as the fundamental patron for design. The need to sell meant that the “quality” of a design was measured based on a third form: did the consumers of a designed object actually like it? Is the quality of a designed artifact determined by a person’s ability to use it?

“Human Factors” became a more important topic, and designers such as Raye and Charles Eames, employed by the furniture manufacturer, the Herman Miller Corporation, started studying the way humans actually used objects in context. Henry Dreyfuss famously turned his attention to ergonomics writing books such as Designing for People (1955) and The Measure of Man (1960).

By the 1980’s this conception of design’s purpose was gaining traction. Don Norman famously published The Design of Everyday things ((originally titled “The Psychology of Every Day Things”)) arguing exhaustibly that the quality of a designed artifact came from a user’s ability to understand it.

By the 1990’s the idea has been taken even further. In addition to the physical attributes of an individual (which could be measured in a lab), and the behavioral psychology of an individual (which could be understood as universal truths about cognition), designers shifted toward an interest in individual understanding that may vary across different social contexts. Design now sought to understand individuals and their mental models at an even deeper level to give them even greater senses of empowerment. “Design Research” came into its own as a topic of study and an official profession.

In the new era, therefore, a new orientation around the “customer” or the “user” grew practices in understanding the individual in physical, cognitive and contextual ways with ever increasing degrees of nuance and granularity. The goal of uncovering and acting on this new, distributed knowledge led to to a design “practice” that saw much fanfare in the corporate of the early 21st century as terms like “Design Thinking” and “Human-Centered Design” entered the collective vernacular.

It is in this late manifestation of design practice that we can see the common themes of neoliberalism fully formed. In particular, we can see the outcomes of a neoliberal worldview across four main areas of design practice:

- Quality: A shift from understanding the quality of a designed artifact from universal (such as mathematical or geometrical) attributes to contextual characteristics.

- Qualifier: A shift from understanding the quality of a designed artifact from the educated eye of the specialist to the lay eye of the consumer and, as a result… (Norman, usability, etc..)

- Study: A shift away from the studio and into the context of use for determining whether an object is well designed. (Design Research / Human Centered Design / psychology, etc…)

- Process: A design process and method that celebrates a “marketplace of ideas” as the core of it’s intellectual engine. (Design Thinking)

As we look in detail at these four areas, we see that each is well represented by trends in late 20th and early 21st century design practice.

Quality: From Universal to Contextual Characteristics.

Quality: From Universal to Contextual Characteristics.

Consider the similarities between these two statements:

“Value is not a property of objects or a quality they possess. Although we talk of objects “having value,” we mean that we value them. Value is in the mind of the person contemplating the object, not in the object itself.” (Dr. Madsen Pirie)

and

“It is in the interaction with people that products obtain their meaning: On the basis of what is perceived sensorially… products reveal cues of how to use them, and they reveal their function. Perceived properties will only be of interest to an individual is that are somehow instrumental in fulfilling needs; only in relation to people we can determine what behaviours a product allows for, and what its primary or secondary functions might be.” (Hekkert, 2007, p.4)

In both of these statements – one representative of a Neoliberal mindset and one of a design mindset from the early 2000’s, we see a contextual state of value. Neither an object’s value (Pierie) or purpose (Hekkert) can be measured in an objective, atemporal sense. The root value is projected by humans in-situ, or as London School of Economics scholar Saadi Lahou ((Installations Theory)) would put it, in “the Installation.”

It is important to remember that neither of these statements are uttered themselves in a vaccuum – both are a response to (and rejection of) prevailing notions that preceded them. Pirie, in his statement goes on to reject the Marxist theory of supply-side value arguing instead that because value can only be measured within a particular physical and temporal context, that a universal calculation would be impossible. Hekkert, and many of the contributors from which his work is made up of – represents a shift away the more universal aesthetic ideas of design’s predecessors. When designers such as Le Courbusier (and others…) argued for an “International Style,” it was a universalist current that carried the day.

Notably, in neither situation are the authors arguing that a solution couldn’t be universal. Rather, they are arguing for a shift away from universal principles of aesthetic to universal methods of problem solving. Both the neoliberals and designers shift their source of “truth” to the individual – neoliberals through an emphasis on perception and choice, and designers through an increased interest in cognitive psychology and, eventually, understanding of local context (citation needed). They therefore construct the argument that IF a universal truth exists, it must be deduced from a study of the way things play out in the real world – not projected from a normative theory of how the world should work.

For a neoliberal, a good system is one in which the individual has more freedom to pursue her goals regardless of what those goals are. To a late 20th century designer, a good product is one that a user can use to pursue her goals – whatever they may be. In this way, both philosophies position themselves as seeking to promote individual agency by crafting systems and practices that define value in context.

Because they exist in systems that localize agency, the measure of value itself shifts: in both cases, the contextual understanding of value now lies in the individual “customer.”

Qualifier: From Designers to Consumers

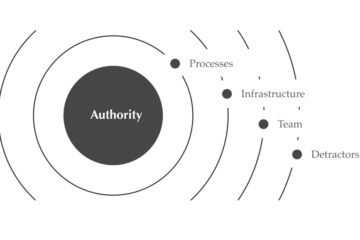

The neoliberal shift toward distributed agents as focal points for information processing and agency reconfigured the way humans working in neoliberal societies think about human networks. In this neoliberal environment, these “agents” became “users” or “consumers” of products and commercial organizations shifted to the “customer is always right” mentality that would win in the marketplace.

With this new orientation of value – value not as something that could be generated within the organization but, instead, was determined by customer interaction – new methods needed to be developed for organizations to collect information about, comprehend internally, and contribute to the production of value. This meant a shift toward a richer vocabulary and new models for understanding human behavior.

Understanding both the desires and the behaviors of agents in the world became paramount, and different types of focuses emerged based on different contextual situations.

In the consumer marketplace, the most important measure of value from the prospective of producers tended to be at the point of purchase.

The push toward emotion in branding led to a greater variability of the messages that people would receive. The product qualities of a particular line of soap may not be differentiated at the scientific level, but the shift from an objective, scientific standard (“does this soap effectively clean hair) to a customer centric perspective (Is the right shampoo for me?) created the imperious for a plethora of differentiated graphic and packaging design. To the extent that brands sought to teach customers about their products – the goal was always in increasing customer savvy to set an expectation that the brand would be best able to fulfill. In the end, though, the decision lay with the consumer – the product design must always acquiesce to this understanding.

In the B2C space, it was not the moment of purchase that most mattered, but the productivity of the user. This led to an increased research about how individual humans used space to better understand the way new objects could be crafted to existing habits.

Herman Miller’s revolutionary designs for the modern workplace exemplified this approach. Designers studied the way office workers organized information in context, then designed a modular set of furniture to meet these needs.

The goal was not to change the way people worked, but to shape the artifacts in the environment to compliment existing practices. It was the assumption that the “user,” in the context of her daily environment, new more about the task at hand than the designer. Simply by shaping the material aspects of the environment around the user’s behaviors and mental model, therefore, would improve the user experience.

Herman Miller furniture also did not seek a universal truth for the design of a workplace. Rather, their modular system pushed decision making to the agents in the context (in this case, the companies and employees) to implement furniture as they saw fit.

As the ultimate goals shifted, a new vernacular was needed: rather than a focus on the objective truth of the product, designers sought to understand the “mental model” of the prospective agent that would decide whether or not to engage with it. The term “affordance” describes the perception of how something in the world acts specifically from the eyes of the user. Unlike previous aesthetic vernacular which may have concentrated more on universal mathematical principles of visual cues, “affordance” is directly related to an object’s function. However, this is an important shift from simple discussions of “function,” which can be more or less tested objectively. Affordance is, therefore, a measure of whether the function of an object is implied to the perceiver within the logic of her mental model ((Similar is the discussion of “display, control compatibility.” Whether an object’s “display” or “control” are “compatible” is ultimately a decision that must be made in the mind of the user.)). “Consistency” as a design principle survives not because it is good in a philosophical sense, but because individuals are more likely to remember consistent patterns and more quickly understand how something may function. “Easy to use,” in itself became a product benefit with which to use customers.

In the case of all of these terms, designers could no longer have confidence their intuitions and training to determine a “good” design from a poor one. Ultimately, everything needed to be tested with users or customers before large investments in production could be made.

Again, the ultimate measure of value was not the aesthetic of theoretical beauty of the objects produced – it was whether they increased the comfort and utility in the eyes of the people who used them. This, again, is a direct reflection of the neoliberal understanding: the most useful solutions empower the agents to work within the situations that they understand best. Ultimately, it is the decision of whether or not to adopt a solution lies with the agent, but modular solutions give the agents more power and flexibility, and are thus preferred in the market.

The best method for proposing a solution, as the Herman Miller designers demonstrated, was to spend time in the local context.This need led to dramatic shifts in where design research would occur and how the design process should be structured. It is this notion that “design” as an industry would solidify around during the latter part of the 20th century.

Study: From the Studio to the Context of Use

Both the industries of marketing and design turned toward understanding the mental models of consumers as the core source of truth and, by consequence, developed methods for getting consumer insight earlier in the production process to mitigate risk.

As an industry, however, design arguably took this idea much further. Supported by an increased production of psychology studies, many in the design industry came to separate the “reflective” from the “behavioral” aspects of human cognition ((Don Norman, “Emotional Design.”)). The “reflective” ((or, as psychologist Daniel Kahneman would later describe as “System 1”)) aspects of psychology referred to the rational cognition and narrative understanding that users had about how the world fit together. This tended to be sufficient for understanding broad goals that customers had, and the types of narratives that would influence buying decisions.

“Behavioral” cognition, however, could only be recalled by a subject in context. This cluster of activities relied on the older habit-forming “reptilian” areas of the brain((for more on this, see Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit)) which managed sensory perception at a much richer level than just rational cognition. Writers such as Andy Clarke discussed more “distributed” forms of cognition arguing, essentially, that the “knowledge” a human possessed did not simply reside in the brain. Rather, as humans use technology – such as a pencil and a piece of paper – to remember something, but keep these artifacts within their periphery, they are, in fact, acting as “natural born cyborgs.”

With this new idea of cognition – cognition distributed into familiar environments rather than simply residing within a person’s head – it is impossible to study a person in a lab or even to draw solid universal rules about the structure of mental models. The information is in context – and a designer can only generate a possible solution by understanding the way this information flows in-situ.

This understanding opened the floodgates for a new type of research – one that came to reside under the broad umbrella of “design research.” Many of these methods, such as “contextual inquiry,” “diary studies,” and “shop-alongs”specifically targeted ways to watch user behavior and get feedback “in-context.”

This also brought a new emphasis to the “prototyping” phase of the traditional design process. Prototypes wouldn’t simply be for designers, engineers, and business people to align behind the specifications or functionality, but should be tested with user and – when possible – in context.

The most radical transition were the introduction of “participatory design” or “co-creation” practices. This brought not only the measure of “quality” to the user, but the construction ((at least, in prototype form)) to the user. The position of “designer”shifted to one of moderator and finalizer of decisions ultimately made (or, at least fundamentally directed by) users or customers.

Process: From Experts to Design Thinking

…this one is more complicated, coming soon…

Conclusion

The neoliberalization of the designer mindset and the context in which design is practice fundamentally changed the way design is practiced. As mindsets shifted from an emphasis on the expression of universal ideals imposed on a system toward the empowerment of agents within the system, designers positioned themselves as the conduit with which agent decisions could be understood and channeled into production.

So long as the agency of the individual is a top priority and the individual is seen as the master of information in context, we can expect the practice of design to center around the user.

As we turn to Part II, however, we see that this fundamental focus is simply a relic of its era. As we look toward a shifting philosophical undercurrent in the West and commercial (and government-influenced) enterprises in the East working their way toward more strategic positions in the value chain((in other words, positions in the value chain where it becomes important to develop internal design competencies)), we can expect the practice of design to again shift. In many ways, this transition has already begun.