…but the lean people and the agile people…

Some years ago, I wrote on my linkedin profile((or in my portfolio or something, my startup was bleeding out and I was looking for a job.)) that I was interested in “the nexus of lean business strategy, design thinking, and agile software development.” To me, these things had a lot in common as they were all concerned with breaking down barriers within existing business structures to find better ways of producing market fit.

What I was starting to realize, however, was that there is a great deal of friction between the agile process and the design process. Nobody in my Scrum Product Owner or Scrum Master training could tell me how the “design process” was supposed to fit inside or interact with the agile process. They offered a few comments about “user interface” design, but everything sounded more speculative than authoritative and definitely didn’t come close to the expansive definition of “design” I was used to from my previous collegiate or consultancy experience.

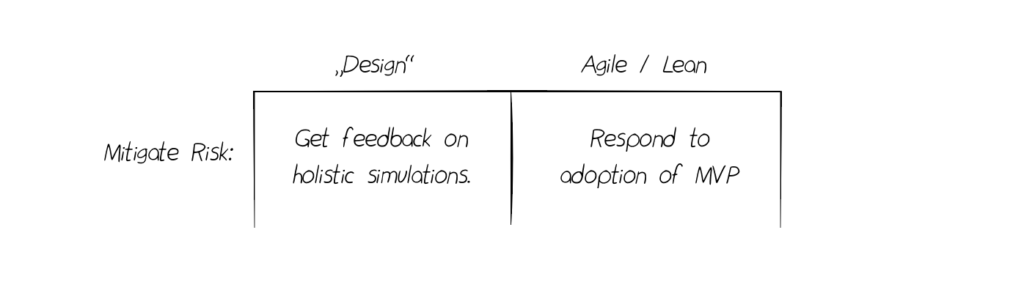

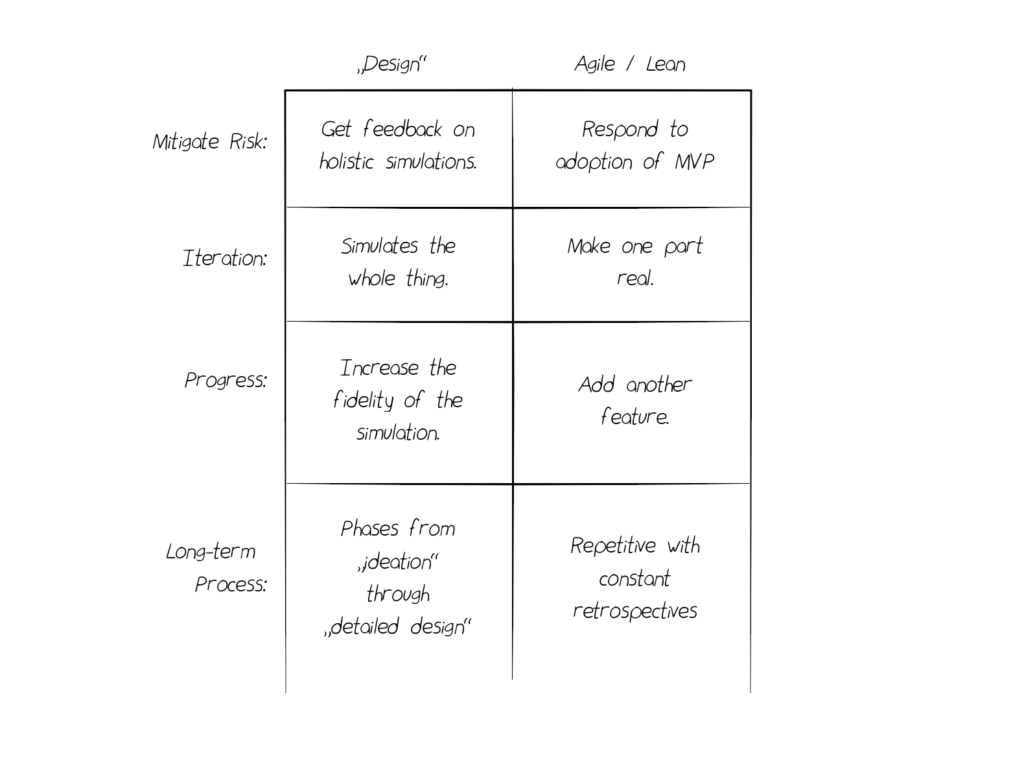

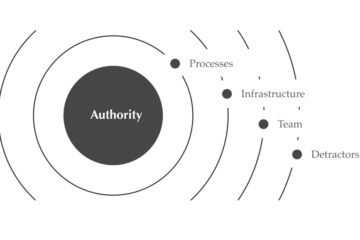

Over time, I came to realize that, while these things seem similar from the outside, at the detailed, practical levels they could not be more contradictory. Before turning to the details of these processes, however, we must analyze how these conflicting ideas think about their core task: mitigating risk.

Design vs Agile/Lean approach to risk.

In the end, both the design and the Lean/Agile approach seek to better find “market” fit. This typically means the private commercial sector, but can also mean crafting internal tools, or product output for government, organizations, or anyone else.

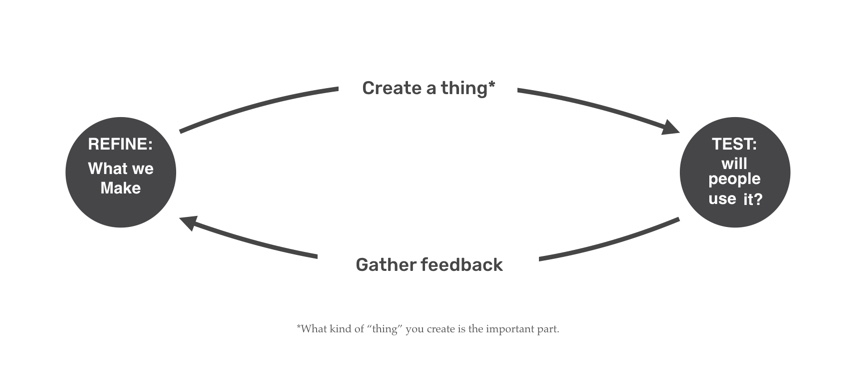

In any case, these approaches seek to see if the things the team is working on will be adopted in the environment they’ve been crafted for. Both take a cyclical approach of creating something small, then forming some type of test to assess market fitness.

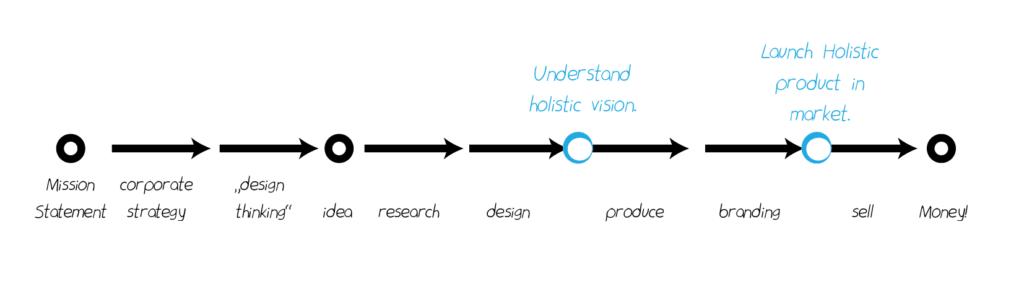

Designers try this by creating artificial but holistic prototypes which enable a value proposition or an artifact to be tested in a fake environment early, but testing in the real world still lags behind a development schedule. This means that real learning has to wait behind that whole linear process.

Traditionally, this hasn’t been terrible because design was less concerned about what the product should be rather than how the product should be. The design process was created under the assumption that the value proposition was true, and set about making something usable, beautiful, and, most importantly, desirable. In the latter part of the 20th century, “design” started trying to fix this by creating new methods like “co-creation” and “participatory design,” which traded output fidelity for a chance to work earlier in the linear process((In other words, we could run “tests” with potential “customers” and “users” to explore what types of problems people had, but they were all much more imaginary. Prototypes made of paper, methods where we built a value proposition with a worksheet or other imagined activity, etc… These practices are extremely useful for starting and holding open-ended conversations with eventual users, but they also come with an organizational danger: they might trick us into overconfidence which becomes an enabling force for an organization that wants to maintain a linear, waterfall process.)). Many of these methods do force a user to prioritize one aspect over another, but the context of the situation (specifically, that the context for the decision is artificial) still makes them fundamentally exercises that measure desirability.

Design likes to concentrate on the overall gestalt of an offering, and, thus, its processes are focused on holistic understanding. In the “Design” phase, designers craft a holistic vision that, ideally, will later be holistically implemented and launched after the completion of the whole development phase.

This becomes a challenge, though, as design tries to work its way up the value chain in 21st century markets. Linear timelines are simply take too much time to go to market, and in many cases, businesses are becoming more humble about their ability to divine the future. Many are starting to question where “user testing” and various market research methods are true enough to mitigate risks for large investments.

The Lean Startup mentality recognized that ultimately Design is best for testing for desirability, and perhaps usability, but not the extent to which people would adopt an offering. Seeing adoption as the biggest risk, Lean created the idea of the “Minimum Viable Product” – a product that focused on finding the most compelling value proposition and iterating from there. Rather than envisioning a holistic goal, the MVP was ‘minimal’ so it could be iterated on quickly. Viability was tested through actual adoption – once a product was deemed viable, it could be expanded upon.

Ultimately, Design believes that something has to be thought about holistically before it can be tried in real life. Agile / lean believes that if the critical kernel of “value” – the value proposition – can be identified, an MVP should suffice to take the next steps.

Whether a team is more interested in desirability or adoption favors, fundamentally influences the direction that their process will evolve – specifically, whether their process will favor holism or fast iteration ((It goes without saying that all teams are interested in both, but this is a question of prioritization. This can be understood in a few ways. The simplest heuristic – though quite blunt is just to see where the organization spends its money. A better way is to see what the organization measures – do subjective measures of “quality” influence project management timelines, or are measure based on producing reliable delivery within increments? If the organization lets “quality” affect its gantt charts, it is probably more of a “design” flavor. If there is an emphasis on reliable delivery in consistent timeframes (and “quality is controlled through release, but not sprint cycles), it is focused on fast iteration)).

Different Philosophies: What is the goal of an increment?

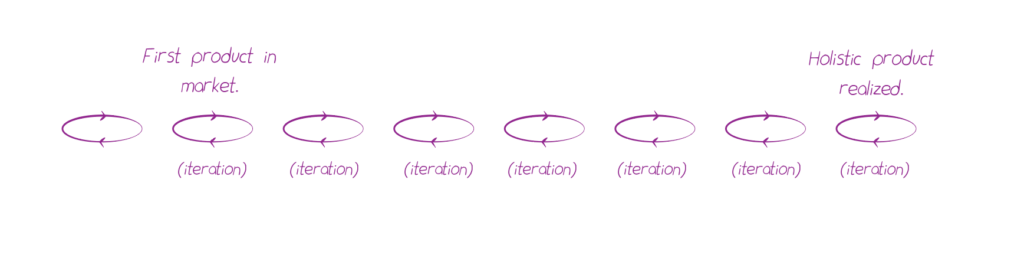

Both systems offer an “iterative approach,” and in both, the iterations attempt to grow from a fundamental core toward something more robust, but that is where the similarities end.

Design: whole, but fuzzy

Agile: minimal, but functional

The first iteration from the Design perspective should feel whole, but fuzzy. It may be a quick, low-resolution sketch, but it has to consider what a holistic experience would feel like. With this simulation, stakeholders and potential customers can respond and collaborate to suggest improvements. The output of a design iteration is, fundamentally, an artifact that can be used to facilitate collaboration and work toward a shared vision.

An Agile/Lean first iteration is minimal, but functional. Whether the product is “right” is determined less by the stakeholders and more by the market itself.

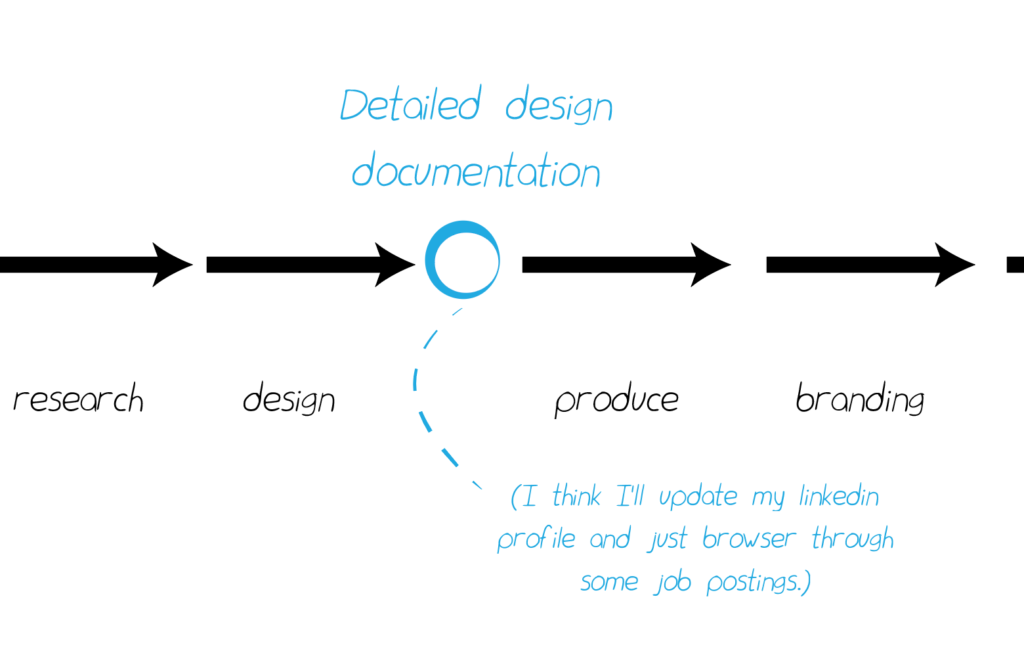

What progress looks like through each process also varies. In the design process, progress looks like increased fidelity – we start with an idea on a post-it, graduate toward a sketch, then a beautiful render, and finally some kind of spec document that can be consumed by an engineering team. On an agile / lean team, we go from idea to functional in a single increment, so in agile, progress means increased product scope with a new type of feature or functionality.

The design process, therefore, is linear, while the Agile process is cyclical. Each goes through cycles, of course, but the Agile increment starts with a backlog item and ends with some software with each iteration. Design on the other hand, needs to go through several phases of fidelity increases before it can be passed off to the next part of a linear value chain where someone else will create the functional version.

Since the output of a successful “iteration” is fundamentally different, design teams and agile / lean teams have evolved completely different approaches to ensure success.

Different goals lead to different processes

In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, the differences are profound.

The tensions really start to manifest in the workflow. Each philosophy optimizes its process based on its goal. Design is concerned with holism, and agile/lean is concerned with flow. Divergent goals means divergent processes. To understand the core friction between these two processes, we need to think about “batch size.”

The concept of “Batch size,” and the roots of lean business strategy and agile come from Japanese factories (mostly Toyota) which needed to maximize output and also provide a certain amount of flexibility in the details of each produced unit. A “batch” represents the total amount of work that is currently “in progress.” Having a large batch of work feels good in theory, because it seems like a lot of things are getting done.

In reality, though, it tends to create waste. Every process has a bottleneck step, and the output of the whole will only be as fast as that step. Improvements that happen anywhere other than the bottleneck step will not produce more output, and increasing the batch size often exacerbates the problem. In the manufacturing sense, a larger batch means store rooms and factory floors need to be bigger to compensate for inventory piling up because of the bottleneck point. In software development, it results in overflowing inboxes and pointless meetings where countless things are covered, few things are resolved, and most people can’t keep track of anything.

Agile and Lean get their flexibility, therefore, not from flexibility within the running process, but from controlling batch size so they can finish an iteration of the process faster. They also repeat the same process over and over again, which gives them the opportunity to have meaningful reflection and improvement on the process itself.

Design is also an iterative-based process, but its goal of being holistic means that each step has an enormous batch-size. These batches are fine when things are at the sketch or post-it level, but they get out of hand as the fidelity of output rises toward the end of a project.

In reality, I’ve yet to hear a designer talk about “batch size” because in design, “efficiency” is rarely a primary concern. As a discrete part of a linear process, it isn’t a huge concern – particularly for the more expansive, strategic projects. For the “detailed design” phase of software projects, things tend to get a little bit grueling((and designers start getting burned out)) as we find ourselves tracking consistency across hundreds of screens and states. Software like Sketch has been evolving as quickly as it can to facilitate this process, but it still gets overwhelming as we prepare for a big delivery.

I know the other medium articles don’t like to talk about this because it is so old-school, but MANY, probably MOST companies still use a linear process for these kinds of things.

Part of the reason is because the devs love it. They want to produce the thing quickly, and they know that business people changing their mind is the largest threat to metric. By having everything documented up front, their asses are covered and then can estimate the number of sprints something will take without having to worry about a “scope change.”

Business people love it too. When they see beautiful, holistic designs at full resolution, they feel like they are heading up a big, important operation.

Designers, of course, also love it because we tend to be measured by others and even put a lot of our own self worth into crafting beautiful visions of the future.

Unfortunately, most of that might not matter.