Welcome to Knowledge in Society – my personal blog devoted to the messy knowledge and human cleverness around us. I borrowed “Knowledge in Society” from the late economist F. A. Hayek’s pivotal 1945 essay

The Use of Knowledge in Society, an essay that personally re-framed the way I understand the world and established a base for the research I continue to do today.

Hayek’s essay, a response to the growing analytical nature of economics, calls into question one of the key assumptions in his field: the notion of a singular, universal, objective knowledge that, if it existed, could help us achieve perfect economic order. Hayek’s task isn’t to dismiss scientific knowledge or the scientific method outright – he believed is useful within it’s scope – but he argues that a different type of knowledge, more distributed, contextual knowledge, needs to be recognized for social science and economic study.

Ambitious Goals

The goal of an encyclopedia is to assemble all the knowledge scattered on the surface of the earth, to demonstrate the general system to the people with whom we live, & to transmit it to the people who will come after us, so that the works of centuries past is not useless to the centuries which follow, that our descendants, by becoming more learned, may become more virtuous & happier, & that we do not die without having merited being part of the human race.

– Dennis Diderot, Encyclopédie

Though Hayek was interested primarily in the state of economics,

The Use of Knowledge in Society responds to a much deeper social trend that had been at work since Diderot, d’Alembert, and and other

enlightenment writers’ work two centuries before.

Dennis Diderot, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and a small host of other French “men of letters” made their contribution to the thinking of the Enlightenment Period in 1751 when they published the world’s first encyclopedia, le Encyclopédie, with the ambitious mission to create a single point of all (at least, western) human knowledge that could be accessed by anyone who could read.

For the first time in Western history, a secular collection of individuals argued that knowledge itself could be curated, classified, and shared! The book and the mission rippled through the 18th century bourgeois society adding momentum the scientific, industrial, and the French political revolutions. It was no coincidence that just 11 years after the end of the first print run of the le Encyclopédie, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations,* a book that came to define another “scientific” field: economics.

We are still considered to be living in the enlightenment period – an era defined by the notion that knowledge is universal, objective, and measurable. Contemporary writers, scholars, politicians, and social scientists attempt to apply these empirical, rational arguments to everything from the proper way to organize a society to the existence of god. Humans may not yet possess it in total yet, but all knowledge is understood to be available to us waiting to be discovered. As documented in the first chapters of Eric Beinhocker’s The Origin of Wealth((To be fair, both the Wealth of Nations, and Smith’s other book, the Theory of Moral Sentiments, offer a very deep understanding of humanity that has been completely overlooked and unfortunately simplified to the point of bastardization by both professional and the armchair economists past and present. Unfortunately, it is often not the writing itself but the social perception of it that defines a legacy.)),** the field of economics in particular evolved to favor an extremely analytical approach to understanding the social sciences.

*

**I review and summarize part of The Origin of Wealth here.

Scientism

“The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.” – F.A. Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society

But can all knowledge systems be fully mapped, measured, and made both accessible and actionable? Hayek argued that this is a form of

scientism, a term he would later adopt for his 1952 book

The Counter-Revolution of Science. He draws a distinction between natural science – where we measure the relationships between inanimate objects in search of measurable, consistent laws – and social science, which deals with the relationships we, as humans, have with objects or relations we have with one another (p. 25).

Hayek’s “almost heretical” assertion in The Use of Knowledge in Society was “to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge…” but that there is another “very important but unorganized…(type of) knowledge: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place.”

Scientism is belief in the universal applicability of the scientific method and approach, and the view that empirical science constitutes the most “authoritative” worldview or the most valuable part of human learning—to the exclusion of other viewpoints. – Wikipedia

As an example, he notes the extent to which theoretical knowledge is only the beginning of the long journey to learning a certain occupation as well as the “knowledge of people, of local conditions, and of special circumstances.”

Hayek was by no means opposed to the collection of data and the attempt to use it to make economic observations. He simply tried to stress the naiveté of scientism. He warns of the degree with which economists in his time – and in ours – tried to make assertions with the belief that their data was complete and stresses the dangers of assuming that discoveries in social science can be as readily applied in social engineering as laws in the natural sciences are to mechanical or electrical engineering.

Behavioral Economics

“We make constant use of formulas, symbols, and rules whose meaning we do not understand and through the use of which we avail ourselves of the assistance of knowledge which individually we do not possess. We have developed these practices and institutions by building upon habits and institutions which have proved successful in their own sphere and which have in turn become the foundation of the civilization we have built up.”

– F.A. Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society

Though the scholastic innovation barely beginning to solidify at the end of his life, I believe Hayek – and Adam Smith for that matter – would have been passionate about the emergent field of

Behavioral Economics. As an “Austrian” economist, both in nationality and school of thought, Hayek was primarily concerned with price as a communication and coordination mechanism that enabled local agents to act without a complete understanding of the systems around them. The Use of Knowledge in Society, however, cites price as only one of the “formations which man has learned to use… after he had stumbled upon it without understanding it.”

Today, we have gained new insights into some of these other “formations” through a new understanding of the way we process and act upon information around us. Among these formations, we look to the mental models, heuristics, and physical artifacts that have emerged at the local level as reflections of factors – economic and otherwise – around them. This, too, is knowledge, and Hayek’s essay argues that though unquantifiable, it is no less important.

This is the type of knowledge that is messy. It is the haphazard pile of heuristics that emerge not from research, study, or rational thought, but from groups of humans

satisficing together.

“Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.”

– F.A. Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society

It’s the expression of this local knowledge in thoughts, words, art, and artifacts that tell us something about the world view of the people that hold it. It hints at the forces that are otherwise imperceptible to the outsider trying to understand a group of not through facts, but feeling.

Knowledge Today

Knowledge Today

As we consider the effect of both our own

Encyclopédie, Wikipedia, and the acceleration of information generation and distribution around us, it is tempting to believe that out of this chaos a comprehensible order can emerge. As the Ubers and WhatsApps of the world drive down

transactions costs, we want to believe that a perfect communications singularity can exist – that we will finally be able to build a perfect, seamless society.

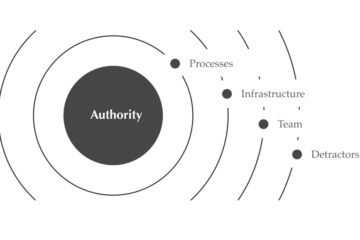

Unfortunately, Hayek’s assertions are just as relevant today as when he penned them in 1945. Though tempting, it’s disingenuous to simply assume increases the quantity and velocity of information is an indicator of organizational progress. The internet is, itself, the poster-child for distributed systems and with it’s efficiencies come chaos, misinformation, and noise. While business outside the firm has always been a nodal, distributed system, there is evidence that even within firms we’re seeing a shift away from strictly hierarchical information systems.

This Blog

As the theoretical tenets of cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, and studies of emergence and evolution trickle into the cultural zeitgeist we’re set to see an increased desire for qualitative assessment and application. In true

abductive form, the design industry began developing

design research methodologies to explore business problems even as behavioral economics was in it’s infancy.

This blog is a dedication to the natural fix of the design researcher. To unorganized, local knowledge. To human cleverness. To things that might be untrue, inefficient, or inconsistent but nevertheless useful. To alternate understandings of the world and the things that make it up – the local circumstances that drive logic that, at times, becomes more bizarre as you unpack it.

It is also dedicated to the methods that we use to understand these quirks in human society. To the practices that help us discover them and the models and theories that allow us to understand and communicate them.

And, to be honest, it is a dedication to things that I, personally, find interesting.

– kyle