Summary: In a rapidly changing world, it is easy to get disoriented or disillusioned about the state of progress. As humans, it is far easier to make judgements relative than objective ones, so a value judgement about the present state of the world is highly influenced by what you compare it to. Those that spend time thinking about how to improve the world feel distraught at the current reality.On the other hand, those who spend a lot of time thinking about history may marvel at the wonderful lives we live today. I argue that seeing historical artifacts in day to day context makes it is easier to appreciate innovations. For instance, though it is still several years old, Uber or Didi still feel like modern marvels because the older model – taxis – are still present all around us.

This essay is a work in progress

I have to admit that I uttered a few choice words under my breath the other day stading in the queue waiting to get through immigration at the Shanghai airport. The lines are long and the process can be quite confusing – the whole thing feels like an enormous waste of time.

Its at moments like these two angels chirping in my ear from each shoulder.

The first is quite quite frustrated with the situation. A liberal and a designer, he is the side of me that can see a better future and is frustrated at how long its taking us to get there. Inefficiencies abound and he notices them all: Why didn’t they put the forms over there? Why don’t they have pens next to the forms? Why didn’t the website say I needed to know the phone number of a local person before arrival? Why…

On the other shoulder sits my conservative self – the self that reads a lot of history and thinks about humans, themselves, as wonders – born into a world trying its best to kill us before our own inner demons can take us down. My historian is proud that I’ve made it almost three decades with all of my limbs and teeth, and appreciates that this alone means I’ve had a better life than most humans in history. He is also the one that has read enough history books about the spice trade, China, and Hong Kong to know that the journey from west to east used to take over a year (if you were lucky enough to actually survive the journey). Actually getting in to China? Many westerners waited years just to gain access to speak with a Chinese official, let alone do business there. A good portion of them died of malaria or other such diseases during that wait.

The historian smiles, “You can wait 30 minutes.”

The designer, though, is stuck on the hedonic treadmill. No matter how great things become, there will always be something to complain about – things could always be better.

The hedonic treadmill, also known as hedonic adaptation, is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes. According to this theory, as a person makes more money, expectations and desires rise in tandem, which results in no permanent gain in happiness.

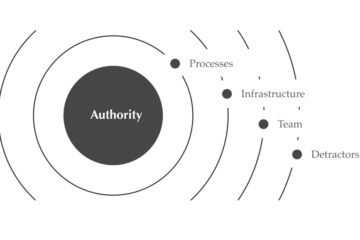

What creates this tension? Why is one of my angels constantly killing himself on the treadmill while the other can sit in peaceful admiration of the human world? I believe the answer lies in the salience of comparable situations.

<>

As humans, we derive our opinions about situations and phenomena in the world less based on their objective qualities than by comparisons. We picture a “norm” in our brain, and judge the situation based on a positive or negative deviation from that norm.

<>

The hedonic treadmill moves this norm forward. Old norms, like planning a place and time to meet somebody, listening to your voicemail messages when you got home from work, or looking up a potential employer’s address at the library and mailing them your resume have been largely forgotten. If my job-search website takes an extra 5 seconds to load, I get pissed.

<>

Even people living in the same place and time period, however, have different norms. At the level of the individual, we reach our understanding of “norm” based on our brain’s diet of information. The historian is comparing the present to a clear picture of the past in his mind; the designer, to a salient vision of the future. Not all norms, however, are tied simply to the media we consume – our context also plays a role.

Maintaining our sense of wonder: Uber and the Hedonic Treadmill.

Sometimes artifacts in our environment keep us from quickly jumping on the hedonic treadmill. Like the historian who is constantly reminded of the past through is readings, these artifacts help us appreciate the novelty of current experiences. Lets look at a place where we’ve managed to retain our wonder: Uber.

Salience describes how easily, quickly, and clearly something comes to mind or can be noticed. The easier something comes to mind, the more it feels like a norm to us, a phenomenon cognitive psychologists call the Availability Heuristic.

Even at the time of this writing (late 2017), people seem to be quite impressed with the idea of Uber. It has been around for years, and the concept of ride sharing for over a century. It is made up of relatively uninteresting technologies used in a way that is no longer innovative or interesting. Yet, inside and outside of my professional life, I still regularly hear that “we want to be the Uber of healthcare,” “the Uber of job search,” and several other such claims. Why are people still so fascinated? How has our society avoided hedonic adaptation in our perception of ride sharing?

My theory: Taxis.

Taxis are still around, they make up a considerable part of our landscape, and every time we see one of these artifacts from the past, we’re reminded of how much that sucked. As long as the concept of ‘taxi’ remains salient, Uber feels like a marvel in comparison. If taxis start to disappear, Uber’s brand could be in trouble! (1)

Dealing with the hedonic Treadmill.

In the professional space, the hedonic treadmill may simply be a fact of life. We have to recognize that it creates distortions in a product experience as user expectations continue to push forward. The unfortunate truth for conservative, slow-moving industries like healthcare, government, and finance, it is likely that improvements may always be unappreciated.

In my personal life, I try to lean more on my historian than my designer – anyone that reads history can compare his experience favorably against a vivid conception of a life filled with problems less trivial. It is my conservative realist streak that keeps me happy and appreciative day to day. But, while the historian is the source of my optimism, the designer is the source of my drive (and also my salary). Thats why I keep them both on my shoulder.

Notes

(1) Not that Uber, as a company, should care. Theoretically, they don’t make money by being perceived as innovative, they make money by being used. Once this change occurs, though, they’ll probably have to have more of a conservative brand orientation to remain relevant to users. If they want to stay as a poster-child of Silicon Valley innovation, though, they’d better hope those taxis stick around.