At their best, magic circles help us ground ourselves, learn new skills, give us meaning and purpose in life, and experience moments of rapture and ecstasy.

Times frequently occur, however, when the members of a group challenge the fundamental structure of a magic circle. Depending on the formality of the circle, this can take some interesting and dynamic forms. We should always remember that while a magic circle is created within the minds of its members, and its bonds are simply based in agreements between them, violations of the norms of these circles can be quite dire and affect the participant even outside the circle’s bounds.

I can think of a few such cases:

- Cheating

- Apostacy

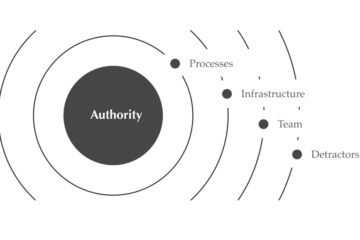

Circles can, however, change. How this is done seems to be quite variable, but I do believe there is one thing that remains certain – for a change to be palatable to members of the circle, it needs to be championed and designed by members of the circle (even if they are receiving advice from those outside it).

Cheating

Sometimes it breaks down.

If you beat me, that is disappointing. But if you cheat – well, that is a scandal! Our harshest social punishments are not for the losers, but the cheaters. In competitive games someone has to loose, and maybe tomorrow they will win. But someone that cheats is an apostate – by violating the rules of the magic circle, they bring into question the circle’s validity as a whole.

We’re all drawn to magic circles as humans, though, and I think that that is for a reason. For a while, I always thought that this was some arbitrary aspect of humanity, but I was listening to a lecture a few days ago on early childhood developmental psychology and the professor pointed out something interesting.

Parents have this weird phrase: “It isn’t whether you win or loose, it is how you play the game.” Why do we say that? There are two reasons.

First, magic circles are a core part of humanity. Without learning how to exist in magic circles, we would couldn’t have money, countries, language, math. Learning to work within magic circles constitutes the training that we need for relating symbols to meanings. When you go to the bank or sit in a restaurant, you’re following a script about how to act, and the waiter/teller is following one as well. If you met the same human on the street, your interactions with them would be different, but inside the magic circle of the restaurant,the script provides a framework for the proper interaction.

The second is because Magic Circles help us build skills in an environment that is perfectly structured to be challenging, yet safe to fail in. Soccer might be fake, but teamwork, athleticism, coordination, discipline, etc… are qualities that make humans successful. The real world may or may not provide the challenges that a kid needs to develop those qualities, so we fake it – we put them in the magic circle with the arbitrary constraints and goals.

This is fundamentally what teachers do – create Magic Circles. The whole goal is to create a regular cadence of success and failure for a person that increases in intensity over time. As a person’s skills develop, they’re faced with challenges gauged so that they´ll have to stretch just a little bit for them. Its also why a kid can perfectly reasonably say “why do I have to learn this, I’ll never use calculus in the real world.” Statistically, that kid is likely to be right, but he’s probably missing the point.

Its also why cheating is acceptable in the eyes of students but not in the eyes of teachers. I’m not sure that kids are always willing participants in the magic circle of school. Unlike the soccer players, they didn’t necessarily agree to stay within the constraints of the arbitrary rules set forth. I could always just pick up the soccer ball and run over to the goal, knocking everyone else down and throw it in, but it is extremely unlikely that even my teammates would accept this behavior – let along the other team.

In school, however, the mechanic of points is an overlap between two different game spaces. The grownups can see the long-game, they want the young members of their society to grow into functioning, independent and responsible adults. Grades aren’t goals in and of themselves, they’re a measure that to track progress toward the goal and to signal relative performance between students. Grownups know that in life, it is disciplined intelligence that kids will ultimately be rewarded for. The lesson not to cheat is just as important of a rule because outside the magic circle, the consequences for breaking social rules is often more serious.

Kids, though, have a different understanding of the rules and goals in this space. Where I went to school, the smartest kids were the ones that cheated the most, and all of the kids knew it.* For those kids, it made way more sense to cheat than to get a bad grade which may have punitive consequences. Most of them ended up in ivy league schools, so it is difficult to say that they were “wrong.”

*Personally, I let other students copy my homework for money. Money was a currency that had value in a larger magic circle than that of school, so it wasn’t obvious to me at the time why I should adhere to the rules in the smaller.

Perhaps notably, psychologists have found that “honor codes” that students sign in college actually do cut down on cheating. It confuses everyone because in absolutely no way does signing a piece of paper create a systemic barrier to cheating. If we consider Magic Circles, though, we can think about signing an honor code as being an affirmation on behalf of the student that she is playing this particular game with these particular rules. Psychologically, this creates a frame for the person and the type of person that she is. Cheating would be a variation from her previous affirmation of self, and to violate one’s own word is an extremely uncomfortable inconsistency that most people want to avoid.

Rule Changes

One could write forever describing examples of magic circles, but for now, perhaps it suffices to simply reflect on the habits of those less experienced tourists.

When we discuss the fundamental magic circles that human societies are built upon – religions, nations, cultures – we have to remember that most of the participants in these games see neither the edges of the circle, nor understand its logic. We have to be careful reading our own values onto others without taking this into account. Adherents in the magic circle need only know that menstruating women are impure, not why they are impure. Asking a person within the circle why a rule is, or asking them to question its validity according to outside logic can be frustrating for everyone involved. Magic circles can be built on delicate scaffolding, and adherents to the circle may be nervous that pulling one jenga block out of the equation could lead to the system’s destruction (I think this is rarely the case, but as humans we seem especially prone to slippery-slope fears).

We have to recognize that outside logic has no place inside the magic circle. If you’re playing make-believe with your kids and you remind them that they aren’t actually a princess and a tyrannosaurus you’re probably not going to get invited back. Those kids, even through they are young, know that they’re human children, but that isn’t the point of the circle. Likewise, explaining to the opposing football team that you picked up and threw the ball into the goal because it made more sense to do it that way won’t get you invited back next weekend.

This is an important lesson. Sometimes we feel the need to change a magic circle based on our personal values. We may feel, for example, that a religious exercise shouldn’t segregate based on gender or we feel uncomfortable when an organization’s culture feels crass or disrespectful to us. In these situations, we have to recognize that bringing outside logic to the table is a less effective method than reinterpreting the logic inside the circle.

A wonderful example is the work conducted by Molly Melching to reduce female genital cutting (FGC) in Senegal. We can make some lovely WEIRD arguments about the “barbarism” of FGC as a practice, but doing so wouldn’t fit in the circle. Nobody questions whether the practice is painful or dangerous, this much is obvious. Most communities, however, will not allow an outsider critique or threaten an important practice that they do not understand.

*Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. An acronym I borrowed from Jonathan Haight.

Before Melching could work to change a practice within the circle, she had to understand the logic that supported the practice. From there, she could lay the seeds for new practices that fit the logic of existing circles.