Guadalajara, Mexico; Mexico City, Mexico; San Salvador, El Salvador;

I grew up on the east side of a north-Texas suburb called Plano. When my parents moved there in the mid 80’s, the Dallas area was booming as oil money started turning into tech industry growth.

This growth brought immigrants from all over the world – South East Asians from Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, Thailand. Tons of Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese, and Korean immigrants. Africans from Nigeria and Ethiopia. Indians, Saudis, Iraqis, Afganis, and, of course, as a southern state, a huge number of Mexicans and other Latin Americans.

We knew some immigrants growing up, but for the most part, my classmates either moved when they were too young to know their home countries or were the children of first-generation immigrants. They were fully American, learning to be foreign through social studies classes, stand-up comedy, and gradual recognition that all of our parents were different. In my 1,300 person high-school graduation class, the most popular last name was Nguyen (14 people in my year if I remember correctly), followed by Tran.

When you’re the white kid in a place like Plano, it can feel like you have one world when everyone else has two. I longed to be foreign or, as a rough consolation, at least to travel. I wanted to be a national geographic photographer, then a pilot, then an Egyptologist. All of my heroes were explorers and archaeologists.

So the first day of every year, every class, I’d sit and listen to poor young, mostly anglo, teachers struggle to get through their first roll-calls. They innocently butchered my classmates’ names in frustration and embarrassment, asking for pronunciation, attempting to get it right a second or third try, making notes on their role sheets. And I would sit waiting, hoping, that just once, they’d mispronounce mine.

My name is Kyle Becker.

They never did. If I was lucky, I’d get the occasional “Beeker” or “Baker,” perhaps, and I’d relish in these moments where I got to correct her. In one math class, I was accidentally called “Carl,” and I went with it for about a week until the teacher noticed on a subsequent roll-call.

Lots of my Asian classmates had actually been renamed for the US. Jackson. Linda. Nick. Maggie. This was helpful to the teachers, who happily penciled that into their roll sheet with a sense of relief, but we always loved to learn their real names too. We’d often struggle just as much as the teachers, of course, but it was cool; a second identity, to some of us, added another cool layer to the worlds we didn’t know.

But for the most part, my fate was sealed: I was just another boring guy with a boring name. My house would look like the ones on TV. My grandparents wouldn’t speak any foreign languages or make any “interesting” food like my friends. We wouldn’t be a part of an “interesting” religion, or have parents with “interesting” stories.

This certainly isn’t a complaint. I’ve had a great life up until now, and I hope it will continue. Most of my friends – from all backgrounds – have as well. The grass is always greener when you’re a kid.

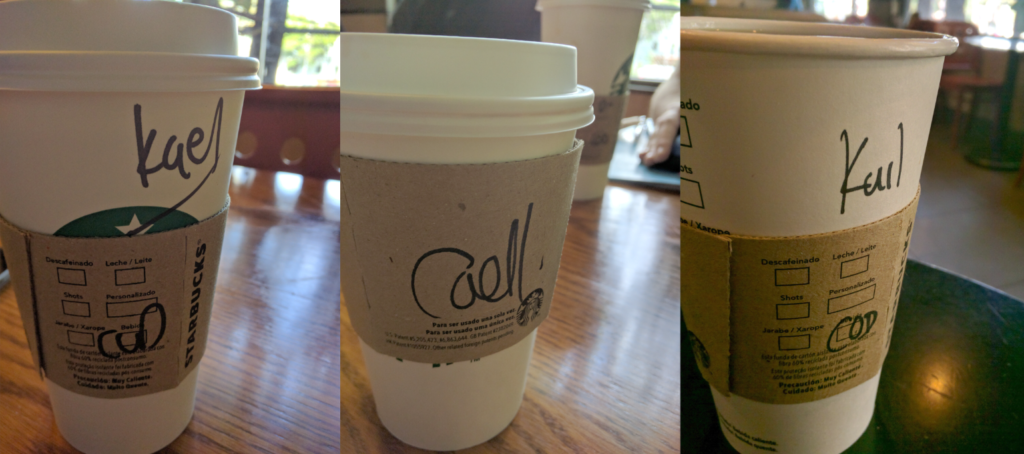

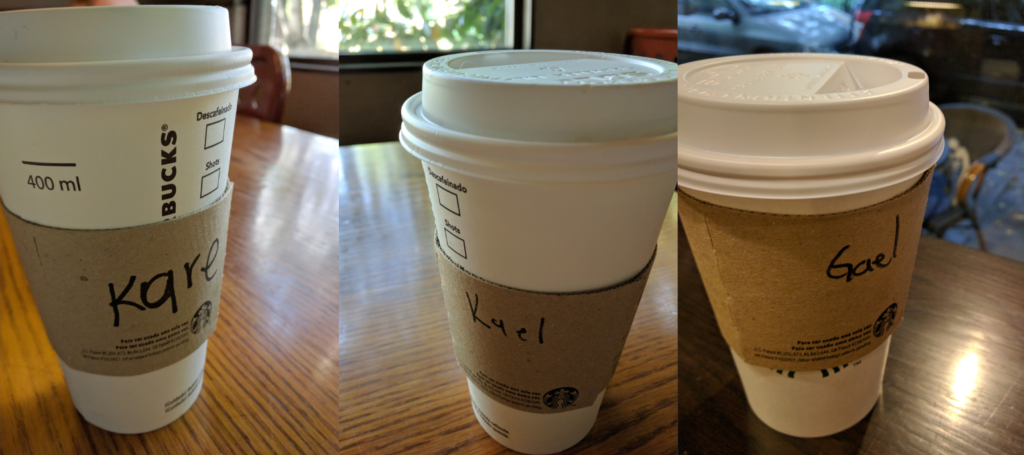

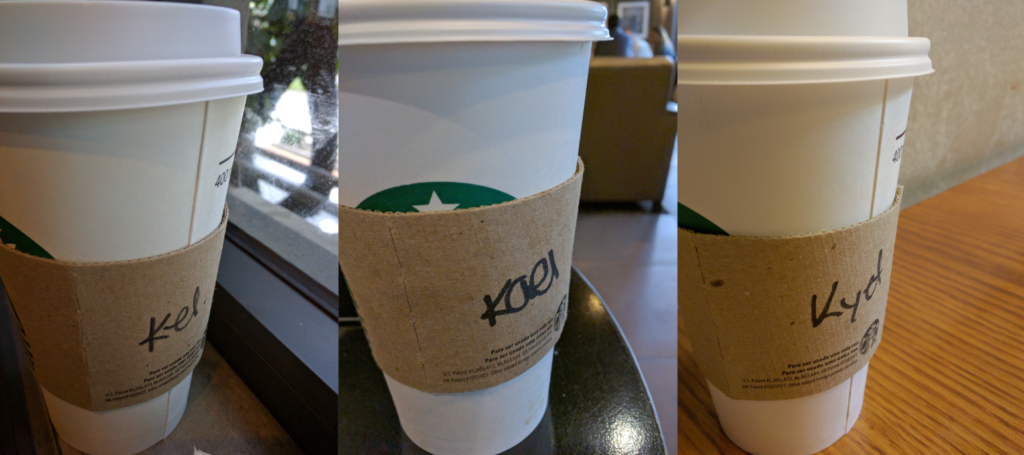

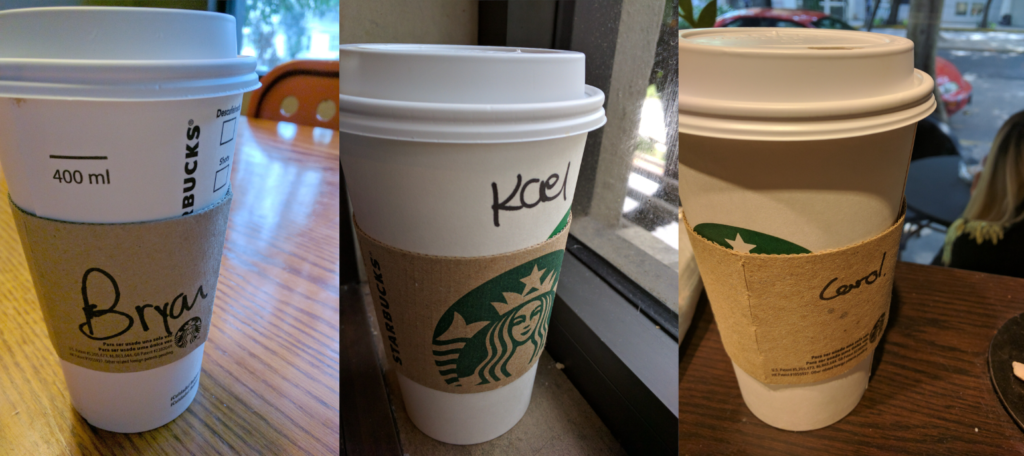

I no longer have to sit through roll-call, but I do look forward to my coffee every morning here in Mexico. That placid stare when they ask “¿Cúal es tu nombre?” and I get to respond “Kyle.” I can’t wait to see what they write. How they’ve interpreted this weird, foreign name heard above the hustle and bustle of baristas and their patrons around them. They try their best, and it is beautiful.

They don’t know how much I enjoy it – maybe few people do. Every once in a while they ask me how to spell it (I actually had to re-learn to say the letter “y” in Spanish so I could help them), but its always a disappointment. It breaks the anonymity.

I read recently that people have started being critical of those teachers struggling through roll-call. They argue these mispronunciations are “micro-aggressions” that damage a student’s sense of identity.

These critics are probably right – I’m not a teacher and I didn’t grow up with a foreign name so I can’t really speak to this. I’m twenty eight now, so I don’t really have to worry about micro-aggressions undermining my sense of identity.

I am proud, though, that it seems to be a distinctly American phenomenon. Learning to live together isn’t easy, and it is nice that people are trying. We’re lucky to live in a country where we can concern ourselves with “micro-aggressions” rather than the simple violence that my classmates’ parents from places like Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Ethiopia, or El Salvador have escaped.

As for me, someone who grew up feeling very plain, I’m happy to finally be an outsider.