DRAFT

This living essay is still in draft form. It is a continuation from my Design and Neoliberalism Introduction – I would suggest reading that one first. Please mind the typos, half-finished thoughts, and informal language. If you have comments, please email them to me. The purpose of this essay is for eventual submission to the Design & Neoliberalism Special Issue of Design and Culture. I don’t know if they’ll be interested, but I’ve enjoyed working on it either way 🙂

Setting the stage for Neoliberalism

Historical movements often take shape and gain momentum by reacting against the movements that preceded them, so a useful first step in understanding the underlying philosophical elements that seeded both early neoliberal ideas and 20th century design in the late 1930’s is to consider what came before.

In his analysis of state development in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott ((Seeing Like a State, 1998)) describes a particular fascination with the desire to see ordered, scientific wholes. Scientific naturalism was of rising prominence, and many movements around the world aspired to bring the clean structured understanding of the natural sciences into the realm of the social. He speculates that many decisions of statecraft were driven by the particularly pernicious combination of three elements:

- The aspiration to the administrative ordering of nature and society raised to a far more comprehensive and ambitious level.

- The unrestrained use of the power of the modern state as an instrument for achieving these designs.

- A weakened or prostrate civil society that lacks the capacity to resist these plans.

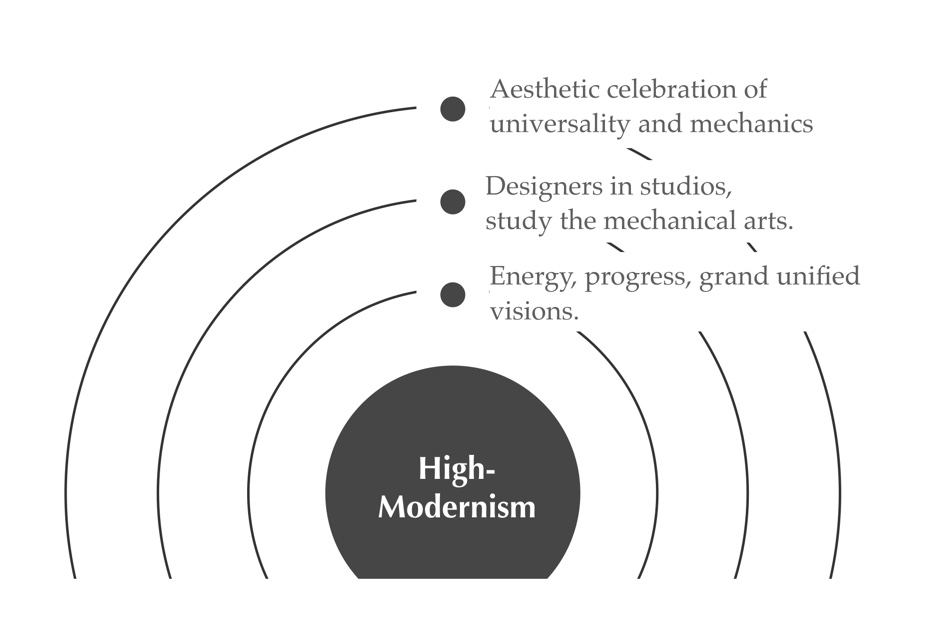

He uses the term “High modernism” to describe the drive toward this comprehensive, administrative order.

“What is high modernism, then? It is best conceived as a strong (one might even say muscle-bound) version of the beliefs in scientific and technical progress that were associated with industrialization in Western Europe and in North America from roughly 1830 until World War I. At its center was a supreme self-confidence about continued linear progress, the development of scientific and technical knowledge, the expansion of production, the rational design of social order, the growing satisfaction of human needs, and, not least, an increasing control over nature (including human nature) commensurate with scientific understanding of natural laws.” (Scott, 1998: Ch. 4)

Scott goes on to describe the justification for this particular era as partially seeded by an adaptation of enlightenment-style scientific reasoning as flipping from a descriptive to a prescriptive understanding. In this new era, scientifically designed schemes for production and social life would be superior to the accidental, irrational decision making of historical practice. This understanding became a justification for the enlightened elite who possessed scientific knowledge and the power to bring order to the world to do so.

Scott’s concept of High Modernism has a certain congruence with Philosopher Zygmut Bauman’s description of the same era as “heavy,” or “solid” modernity. He describes the heavy modern era’s obsession with “shaping reality after the manner of architecture or gardening; reality compliant with the verdicts of reason was to be ‘built’ under strict quality control and according to strict procedural rules, and first of all designed before the construction works begin. This was an era of drawing-boards and blueprints – not so much for mapping the social territory as for lifting that territory to the level of lucidity and logic that only maps can boast or claim. That was an era which hoped to legislate reason into reality, to reshuffle the stakes in a way that would trigger rational conduct and render all behaviour contrary to reason too costly to contemplate.”

It was a time, therefore, where telos reigned supreme, but it was a telos concerned with an ideal of a higher order. The pursuit of this order in all forms was as absolute as it was hierarchical, and served not only as the method for production of the day, but also a mental model for the world. Bauman reminds us that “The way human beings understand the world tends to be at all times praxeomorphic: it is always shaped by the know-how of the day, by what people can do and how they usually go about doing it,” and describes Ford automobile factory as the quintessential exemplar of this idea “with its meticulous separation between design and execution, initiative and command-following, freedom and obedience, invention and determination, with its tight interlocking of the opposites within each of such binary oppositions and the smooth transmission of command from the first element of each pair to the second – was without doubt the highest achievement to date of order-aimed social engineering.”

These theories were nothing new in the early 20th century, but they came to their zeniths in many ways through the establishment of more ambitious forms of statecraft – most notably through the celebration of Keynsian economics and New Deal politics in the US, the rise of bolshevism in what would become the U.S.S.R, and fascism in the European states. While these political forms varied dramatically in their details, they shared a common faith in the imposition of political and economic order through centralized bodies and beliefs in the universality of common standards that could be understood through the scientific method and imposed in a top-down manner.

Design in this time period

“Design,” as the practice and industry that we consider today, began to take form during this time period of the early 20th century, and we can look to a number of movements in art and design that philosophically mirrored “high modernist” ideas.

It was primarily through discussion of “form” that the shift toward a rational, scientific understanding of the world was considered. Prior to this era, aesthetic considerations in the commercial realms of both product design and architecture such as Beaux Arts or Art Nouveax favored elaborate decorative ornamentation.

Around the turn of the century, these styles began to be challenged by ‘modernist’ movements. Adolf Loos, friend of Edward Sullivan, famously criticized ornamentation as “criminal” for its’ propensity to simply invent trends for the sake of marketing. As the world moved on from WWI and looked to rebuild, a new spirit was needed for the aesthetics of the new era they wanted to create.

Designers and architects of this area found this spirit in “Function.” As early as 1896, American architect Edward Sullivan had written his now famous claim that form in nature follows not decorative appeal, but from function.

“Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or the open apple-blossom, the toiling work-horse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law. ((…Where function does not change, form does not change. The granite rocks, the ever-brooding hills, remain for ages; the lightning lives, comes into shape, and dies, in a twinkling.

It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.“))” – Edward Sullivan, 1896

As the 20th century progressed, the alignment of an object’s form to its “function” could serve as the barometer for good design. Function was the pure essence of an artifact’s being – anything that did not contribute to an artifact’s function should be questioned.

Central to this understanding was the metaphor of the machine of the Industrial Age. The simplicity and purity of the an airplane’s wing or a motor’s cylinder were products of scientists’ mastery over Newtonian physics to the extent that engineers could produce these artifacts with a high level of precision and consistency. There was an amount of complexity to consider – heat, air pressure, and other factors needed to be taken into account – but the variables that needed to be understood to craft functioning machines could be worked out more-or-less by a small group of engineers working in their labs.

An added benefit of the Newtonian machine as central metaphor was its universality. Mechanical physics was mechanical physics – these laws worked anywhere in the world ((There were, of course, more experimental ideas of physics, but in terms of pragmatic mechanics, the tolerances of a production machine could overcome most of this viability. Few people needed to pilot their Model T to the top of Mount Everest)). An artifact designed based on the laws of function could have an aesthetic value independent of culture – and could truly be worthy of the moniker “International Style.”

“Function” could be either a simple understanding of function in the absolute sense (the function of an airplane is to fly) or the orientation of the function in relation to a human (the function of an airplane is too transport humans in the air) – coming to an understanding of the orientation of this logic is fundamental to understanding the shift that would occur over the course of the 20th century.

An older understanding of “Form follows Function,” represented by Le Corbusier’s sketch, is an argument against ornamentation.

Notably absent in design discussions of this era was the effect that a designed artifact would have on the humans using them. “Function” was defined by the mechanical task at hand: the function of the airplane was to fly, the function of the automobile was to move. To the extent that humans were considered at all, they were mechanical measurements of mass and function just like everything else.

To the extent that humans were anything more, they could be considered problematic. – humans tended to be disorganized and their individual wills could not be trusted. The goal was to push individual humans toward more scientific rationalism, and a good way to do this was through the design and distribution of rationally designed artifacts. Perhaps the quintessential messenger of this new idea was Swiss Architect and visionary Le Courbusier. Corbu left no question about his understanding from which truth in design emerged.

” The despot is not a man. It is the Plan. The correct, realistic, exact plan, the one that will provide your solution once the problem has been posited clearly, in its entirety, in its indispensable harmony. This plan has been drawn up well away from the frenzy in the mayor’s office or the town hall, from the cries of the electorate or the laments of society’s victims. It has been drawn up by serene and lucid minds. It has taken account of nothing but human truths. It has ignored all current regulations, all existing usages, and channels. It has not considered whether or not it could be carried out with the constitution now in force. It is a biological creation destined for human beings and capable of realization by modern techniques.”- Le Courbusier ((Quote taken from James Scott’s “Seeing Like a State))

As neoliberalism entered the philosophical stage, many of these ideas would be challenged. Industrial designers like Henry Dreyfuss and corporations like Herman Miller Co. turned toward studying individual humans with greater depth first in an ergonomic sense and, eventually, in a cognitive sense as well. As these focuses shifted, the measure of value for a designed artifact would shift from an a simple appreciation of an object’s aesthetic as its representation of mechanical function toward a user or customer-centric orientation. This shift, however, was not simply a trend in design, but design’s interpretation of a broader shift in the way the human was seen to relate to society.

Next: Ch. 1.2; Neoliberalism Challenges the Centralized Structure