More than logic, humans base value assumptions on deviations from established norms. Stories are persuasive because they provide a platform for an artificial experience that can shift a person’s perception of “Normal.”

I: What “Normal” is and why it is important

Using logic to solve tough problems is one of the things that sets humans apart, and most of us are proud of a heritage that favors science, logic, and reason over superstition and narrow-mindedness.

The reality, though, is that logical decision making carries a cognitive load that most of us aren’t willing to devote to every tiny decision that we make. Instead, our brains have evolved a complex pattern-recognition system to deal with this problem. Imagine this situation:

You walk into a large, dark room with about 50 other strangers sitting at tables. Somebody tells you where to sit, and when you sit down, another stranger asks you what you would like to eat. After they have brought you some food, and ensured that you have gotten everything that you’ve wanted, they bring you a piece of paper with a few numbers on it and then walk away. What do you do?

This is a pattern that, by now, most of us recognize and a choreography that we’ve grown pretty comfortable with. The first time that this happened to most of us we were very young and, luckily, our parents shepherded us through it. Through a lot of repetition, we added this pattern to an extensive library of patterns that we keep in our brains and when we find ourselves in situations like these now, we intuitively know to reach for our wallets.

We also develop shortcuts for dealing with patterns that are familiar to us. Cognitive scientists call these mental shortcuts “Heuristics,” some common examples are “rules of thumb,” “educated guesses,” “common sense,” or “stereotypes.”

“Tip waiters 20% at restaurants,” is a common heuristic: I never have to make a decision about how much to tip a waiter in the moment, I just always follow the rule (I still don’t know how much to tip pizza delivery men, I always panic when they ring the doorbell!)

Over our lifetimes, each of us develops an entire library of patterns that help us negotiate social relationships, financial decisions, and more mundane tasks like driving to work.

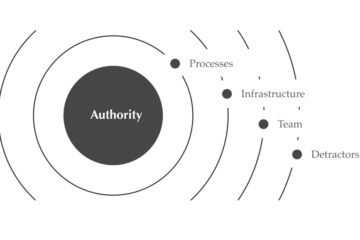

Eventually, we compartmentalize “normal” things, things that fit into recognizable patterns, to shift our focus to outliers.

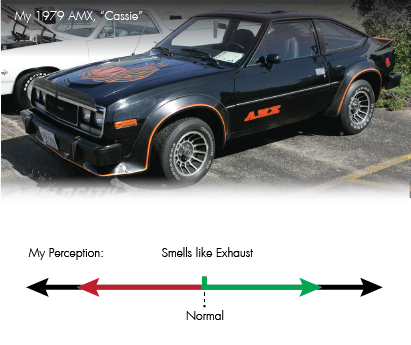

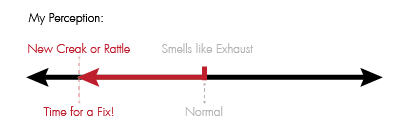

My first car was a 1979 AMC with so many creaks and rattles that it was a little surprising they let me drive it on public streets at all! Plus, every time I started the engine, the whole thing smelled like exhaust for a few minutes, though over time I learned not to notice.

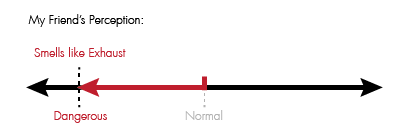

Whenever a friend would ride with me somewhere for the first time,though, they’d head a rattle, or smell the exhaust and turn to me to ask “is that normal?”

Of course, I knew all of the innocent creaks – and if it was “normal,” I assured my friend that we would be fine. Whenever we heard an abnormal creak, though, I knew that it would be a long weekend in the garage!

IIa – Shifting Norms

Progressive and Regressive Deviations

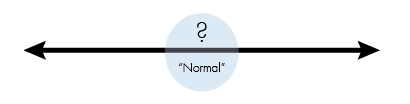

We know that when things deviate from the norm, we should start to pay attention, but when we experience something that we are unfamiliar with, as my friends did riding in my car, we have to look for a definition of what “Normal.“ Once “normal” is re-established, we use it as an anchor to from which to assess our current situation. As it turns out, it is very easy to manipulate someone’s opinion by shift their perception of “normal.”

Clever negotiators leverage this idea with a technique called “Priming.” The technique exploits a shorcut called the Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic. The Anchoring Heuristic describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily on an initial piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions(2).

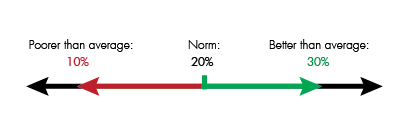

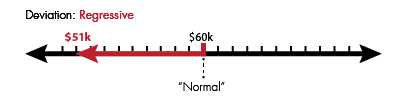

You walk into my office to interview for a position. I tell you that a position like this normally pays a salary of $50,000. You counter by telling me that you are exceptionally well qualified for this job, and would like to be paid $55,000. If I offer you $51,000, who “won” the negotiation?

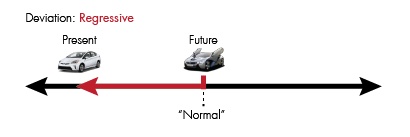

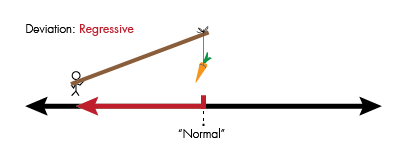

When psychologists run tests like these, most people feel that $51,000, is a pretty good deal because you received a better rate relative to the norm. This is a Progressive Deviation because the offer is better relative to the perceived norm.

How would you feel, though, if I started out saying that a position like this normally paid $60,000? Suddenly, $51,000 doesn’t feel like a $1000 gain, but a $9,000 loss! The opposite of a progressive deviation, a Regressive Deviation happens when we perceive the situation as less optimal than our perceived norm.

Since our brains have been trained to look for an outlier, we’re really more interested in the deviation between the norm and the offer than we are in the nominal offer itself. When the “anchor” moves, the frame of reference shifts!

In situations like job offers that happen at the beginning of a of a relationship, it is usually best to leave the negotiation table with a progressive deviation making the establishment of an anchor all the more crucial. For this reason, many negotiators cite research as the most important negotiation tactic.

If you may make a counter argument by saying that your last job paid you $55,000, you’re actually trying to shift the anchor point for our conversation.

IIb – Simulated Experiences:

Game Spaces, Second Acts, and Design Consultancies

Most of us don’t spend that much time around a negotiation table, so doing research isn’t our primary way to establish norms. Instead, our Pattern Libraries serve as the anchor to measure deviations against. While this is a sensible decision-making habit in most situations, when we confront completely new data, the lack of framework and previous experience can tempt us into squeezing new data into old patterns.

But there is a hack.

The human brain resets it’s criteria of “normal” to new contexts and systems amazingly fast as long as those systems are immersive, so perceived norms be manipulated in these situations as well.

In an experiment, researchers sat a participant in a chair facing forward with a desk in front of them. A researcher in front of the desk (visible to the participant) a tapped the desk lightly and for every tap, another researcher, not in view, gave the participant a light tap on the back.

The researcher in front tapped the desk three times. The fourth time, the researcher pulled a hammer from behind his back and swinging it as if he would strike the table – the participant flinched every time.

If we build an experience that is immersive enough to trick the brain, we get a clean slate to establish a new set of norms. What does it take to craft a believable space?

Game Spaces:

One of the most important ideas for the concept of shifting Norms is the Game Space. A Game Space is a place where a new set of rules or laws is established that differ from reality. These rules can be anything as long as they are:

1. Consistent

2. Agreed upon by everyone sharing the game space.

When playing games, participants must leave previous logic behind, and develop strategies based on a new rule set.

In soccer the rule is that nobody can touch the ball with their hands. When you arrive at the field, of course, you can carry the ball, but once you’ve entered “the game,” only your feet are allowed. When the game is over, you are free to pick up the ball again to leave.

A transformation that happens in the game space.

Learning to play soccer for the first time is awkward: we normally don’t think about kicking as the primary way to move an object. To deal with the contextual constraints of the game space, though, your body learns a new way to interact with that object and new strategies for accomplishing a goal. In this instance, you leave the game space with enhances health and dexterity. What sorts of skills do you hone when you leave a Wall Street Simulator game?

Second Acts

In a story, the Second Act is usually the point when a character enters a Game Space: a place where a new set of rules or Laws is in play. The First Act Break – the point where the first act ends and the second begins- is generally marked with either a change of scenery (think Luke Skywalker leaving Tatooine) or an unexpected change in the character’s abilities (Peter Parker gets bitten by the spider). The character usually spends the second act learning how to get by based on these new contextual constraints. It is usually the Third Act that the hero returns to apply his or her new set of skills or outlook to the original problem.

It is a common rule in Sci-Fi movies that pretty much any technology will be considered “normal” in your story as long as the audience sees it within the first 10 minutes.

Design Deliverables

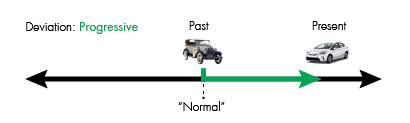

In the design industry, the concept of “now” is a very slippery topic. Because of the lag-time between designing a product and seeing it on the shelves of a store, designers train themselves to “see” the world 2-3 years – or longer in the future.

More importantly, designers learn to visualize, through story, workshops, and imagery, visions the future could be for all stakeholders involved. This can have a dramatic affect on the way that an organization views themselves. Organizations that spend too much time looking at the past, can have an overly optimistic view of their current state.

By creating a new vision, designers move the anchor from the past to the future. In the same way that our negotiation went from feeling like a $1k gain to a $9k loss, designers can make a company that feels innovative relative to past standards begin to feel “behind” relative to the future that could be.

Our entire industry is built upon making the current reality look like a regressive deviation from the future that could be.

III.Implications:

If manipulating our sense of normal is so easy, and we’re so prone to becoming motivated or depressed based on the progressive or regressive deviations of those norms, it puts a huge responsibility on us to tune the norms that we create to reflect the outcomes that we would like to see.

A few years ago I had a spirited debate with a close friend of mine about using legislation to alter the perception of homosexuality in the United States (at the time, 2011, he was studying law at Berkley).

I am generally of the more Libertarian persuasion, so I was curious about the importance that the LGBT community placed on becoming allowed to legally “marry.” To argue for equal treatment made perfect sense – things like legal provisions for seeing somebody in the hospital, the ability to adopt children, and, of course, tax breaks are important rights that anyone should have.

With the “definition of (the term) marriage” such a sacred issue to certain religious constituencies, wouldn’t it make more sense to argue for civil unions to have have the same legal implications as marriage? But why is the term “marriage”so important?

He argued that “Marriage,” as a word and as a concept was as important, if not more so, than the rights that came with it. In our culture, Marriage is considered a Norm – and people who become married are perceived as Normal. By extension,the perception of unmarried couples as regressive deviations from that norm, it can have a catastrophic negative affect on the psyche of those individuals.

If the goal of the LGBT community is to be accepted, issuing a law is one strategy way to level-set that perception. In particular, it means young men and women questioning their own orientation see that what the broader society deems “acceptable” may be wider than the opinions of their parents or local community.

I think that my friend was right – and several years ahead of my thinking – about the way that legislation can reset the idea of what is “normal”for a society (3). My position was logical, but humans do not assess norms based on logic.

Many of my friends active in the feminist movement have similar feelings about the representation of women in media. If members of society draw norms so heavily from stories, movies, and games, then manipulating those fictional representations is a way to change what people notice about reality. Walking into a business completely run by men is no longer the “norm” that we expect and overlook, but a regressive deviation that nags at us to fix.

Conclusion:

There is a saying that many in the business and engineering communities have heard all too often: “you are what you measure.”

If you pay somebody a commission based on the number of bridges they build, they will build more bridges of lower quality. If you pay them a commission based on the amount of weight a bridge will carry, the bridge will be high-quality, but there will only be one of them!

We often talk about this balance shift revealing a truth about incentive and reward systems, but there is a more subtle heuristic that is also at play. Learning to manipulate the way people, and societies of people perceive what normal should be. Learning the fundamentals of good games and stories can be the first step in that direction.