“It was God’s prerogative to make a world suitable to His governance. Men govern a world already in being, and their controls may best be described as interventions and interferences, as interpositions and interruptions, in a process that as a whole transcends their power and their understanding… The actual situation…is the result of a moving equilibrium among a virtually infinite number of mutually dependent variables.” – Walter Lippman, The Good Society, 1938″

Scholars of Neoliberalism often cite the so-called “Walter Lippman Colloquium” held in Paris in 1938 as the foundation of the term in its modern sense. Lippman himself was the author of The Good Society, a book published in 1937 which celebrated liberalism over other political ideologies popular at the time ((Tucker, 2017)). Notable attendants at the colloquium were Ludwig von Mises and Fredrick Hayek – two influential thinkers that would go on to outline and lay the groundwork for a movement that would grow to peak in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

As a whole, the movement built on the ideas of classical liberalism that had emerged primarily as anglo-saxon ideas of the 18th century Hobbes, Locke, and Smith ((check, cite)) which were heavily influenced by Continental European (in particular, French) thinking and revolutions in both The United States (1776) and France (1989-1799). These movements re-laid the groundwork for philosophical concepts that underlie the modern understanding of the relationship between humans and nature, humans and each other, and humans and their governing institutions.

The zealousness of neoliberal ideas between the middle and late 20th century may have formed in large part as a contrasting ideal to the Anglo-Saxon world’s growing rivals. In Neoliberalism’s early years, Toryism, Fascism, and Socialism were on the rise in Europe – trends that Lippman specifically sought to challenge in his book and conference. In the post-war era, Neoliberalism found a new rival in Communism.

Many of the core tenets of Neoliberalism, including an emphasis on the individual, a push toward universal principles (rather than designs), a reduction in the scope of state governance and a celebration of emergent order through marketplace dynamics, can be viewed as a direct challenge to the core values of 20th century centralist ideas.

As the movement matured and gained momentum, an increasing number of institutions grew to support Neoliberal values (in principle if not in name), among them academic institutions such as the Chicago School of Economics and political think tanks such as the Cato Institute, (more… more…).

The relationship between Neoliberal ideals and economic success is hotly contested. Proponents of Neoliberal ideals often present the causal claim that “liberal principles in economics—the ‘free market’—have spread, and have succeeded in producing unprecedented levels of material prosperity, both in industrially developed countries and in countries that had been, at the close of World War II, part of the impoverished Third World” (Fukuyama, 1998, introduction). That the United States grew to such economic dominance the late 20th century at the same time as a shift toward Neoliberal policy appears to support this claim. Other opinions more closely resemble former Singaporean president and geopolitical savant Lee Kuan Yew’s note that the success of the US has been the result of “geopolitical good fortune, an abundance of resources and immigrant energy, a generous flow of capital and technology from Europe, and two wide oceans that kept conflicts of the world away from American shores.” (Allison, 2013)

We will leave the direction of causality to the geopolitical scientists – for our sake, it will suffice to note that a substantial part of design discourse in the late 20th and early 21st century has grown within “The Garden” of Neoliberalism’s rise – an idea we will explore below.

Before turning to the environment, however, it is useful to understand at a deeper level the philosophical rationale and values that underlie Neoliberal ideas. While acting proponents of Neoliberalism focused primarily on the translation of these ideals into political and economic systems, we will also see how these values have shaped design philosophy and practice in this era.

While there are many flavors to neoliberalism, most agree with a few philosophical ideas that evolved from older liberal ideas and and took on economic and public policy implications in the contemporary era. In the context of design, we should consider two effects of Neoliberalism which I refer to as “The Seeds” and “The Garden.”

The Seeds

The ideals and philosophical constructs that Neoliberalism shares with design thinking and practice.

The Garden

The environment that Neoliberalism as a dominant economic and political idea constructed in the late 20th century design would grow in.

The Seeds

The core of neoliberal philosophy re-orients the focus of human systems around the agency of the individual. Neoliberals argued for this orientation most notably in two areas: individualism as a moral political ideology, and individualism as a way toward economic efficiency.

The neoliberal political orientation was in many ways a thread from earlier liberal movements that laid the groundwork for the concepts of “citizen” and “private property” in western Europe several centuries before. ((Insert some Scott in here, and hopefully some Charles Taylor)).

For academics like Hayek, systems of distributed agency such as markets provided more than a simple mechanism for the allocation of capital and resources – it was itself the primary means for which knowledge of a complex world could be generated and most efficiently used by humans. In his 1945 essay The Use of Knowledge in Society, Hayek argued that because the world was filled with incalculable amounts of dispersed and often contradictory information, it was only at the local level where reality could be seen and the best decisions made. A centralized authority could never know what was best, because it could never understand more (let alone enact policy better) than a particular person on the ground in a particular situation.

This humility set the stage for neoliberals to argue that the best possible outcomes for the individual – and the society as a whole – manifest when power is centered within the individual. Any over-arching structures that limit the ability of the individual make the system both coercive and inefficient.

There are three overarching ideas of neoliberalism that fundamentally shaped the way design is practiced today. The first is a new understanding of where information comes from: neoliberals believe that information is distributed in the world, and only agents in context are suited to efficiently consume it. The second is a notion of order: because information is distributed in the world, order comes not from a centralized design, but emerges as the conglomerate of agents acting in local situations with limited but contextual knowledge coordinating with other agents in close proximity. Third is a position on control systems that regulate the roles of these agents in relation to centralized authority: because order tends to “emerge,” order cannot be designed by a central planner. Control systems should, therefore, simply consist of minimal regulatory principles that can be exercised in a consisted, predictable way across the system. With a deeper understanding of these three principles, we can see how they have influenced design practices of the modern era.

Distributed, Contextual Knowledge

Today it is almost heresy to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. But a little reflection will show that there is beyond question a body of very important but unorganized knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. – F. A. Hayek, 1945

Neoliberal theorists were highly critical of the confidence their opponents gained from the high-modernist conceptions of scientific knowledge. It wasn’t that neoliberals abandoned scientific universalism – in some sense, they took the concept to new levels. Their critique was in the human attempt to apply “scientific” principles to social engineering with the expectation that such a narrow understanding could result in a positive outcome.

The problem was one of complexity. By the middle of the 20th century, scientific “laws” found in in natural sciences such as chemistry or physics could be consistently enough relied on to effectively engineer machinery with increasing degrees of complexity and precision. The centralized collection of knowledge of natural sciences meant that the same steam engine created in the UK could run in Tokyo or Rio de Janeiro in exactly the same way. The same mechanics applied, and the same engineer could operate it in any environment.

According to Hayek, most disputes in economic theory and economic policy had their common origin in an erroneous attempt to transfer the habits of thought that were developed to deal with phenomena of nature to social phenomena ((The Use of Knowledge in Society…Also, I need to double check this in context to see if it still fits with my argument here)). Implicit in this assumption was the notion that – in a way similar to an engineer with a command of physics principles can design a machine – a social engineer would have access to the information needed for the design of effective social or economic policy.

Hayek argued that the no planner could be so smart because the type information that would needed for such designs could never be centralized as so much of it was specific to the particular circumstances of time and place. He noted that:

It is with respect to this that practically every individual has some advantage over all others because he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active cooperation.

Lippman too criticized this idea in his opponents whom he accused of desiring to live under a “providential” state ((Lippman in particular was responding to fascistic and communistic governments and sympathizers which were growing in popularity at the time. About communism in particular, he argued that one would have to have “providential,” amounts of knowledge to orchestrate such an endeavor.)). It was simply impossible to amass all of the information that would be needed for a centralized plan, and even if it were possible, there would be no human that would be able to comprehend it.

The concept of distributed knowledge presents a challenge to those that feel the need for order or the desire for a society to achieve certain ends. Neoliberals, however, provided an answer to this in their metaphor of a new understanding of order, an order that emerged from the complexity of the system itself.

Emergent Order: A belief in the Invisible Hand

While neoliberals argued that an order cannot be imposed on a system, they believed order is possible – it simply emerges as the sum total of individual agents acting within local contexts with local knowledge.

This concept takes different forms and metaphors in conversations about economics in particular in the “marketplace” idea. Without a centralized planner to direct the allocation of material resources, a shifting understanding of value (measured in “price”) enables material goods to flow through a system. In a marketplace, an object is assigned a value based on its merits in the eyes of the individuals at present. Neither the item’s cost, nor history is considered, and the value of the object is fundamentally dependent on the assessment in that moment.

Wedged firmly in the ideology of liberals of all stripes is the “invisible hand” of the marketplace which pulls capital and labor toward its most effective ends. Individual actors within the system do not need to see this hand, or know the direction not pulls them in – acting with their own ambitions within their own spheres brings them into a coordinated choreography with the economic system as a whole((The Anglo fascination with the marketplace has been studied in great detail by academics in recent years. Geret Hofstende, in his book “Software of the Mind” which looks at differences in values between members of different cultures notes the different between Americans and British ideas of the market place and those of even close-by cultures such as the Germans or the French.)).

Neoliberals extend the marketplace concept to discourse itself with the concept of the “marketplace of ideas.” In this marketplace, any interlocutor can show up and make her case regardless of her background or qualifications. It is the merit of her arguments, proponents say, that should carry the day – not her background.

The concept of emergent order, therefore, displaces the the idea of “universality.” The system as a whole learns to appreciate types of “value” as universal mechanisms, but the value of a unit in this system – be it an artifact, a currency, an hour of someone’s labor, or even one’s own freedom – flexes over time based on the context that that unit is in. There are no universal laws about the value of an object, only universal principles for how that value may be determined in context.

By shifting the idea of value to a contextual understanding – and an understanding that no centralized system could ever really comprehend or execute on – the roles of both the agent and centralized bodies was forced to change. The very understanding of “knowledge” itself needed to change from the simple recording of information into the need for a higher-level of decision making based on principles.

Governance through Principles (Not Plans)

While the early 20th century held that it was the role of centralized control systems such as governments to use scientific knowledge and rationality in the pursuit of dominance over nature and human nature, by the middle of the century the conversation had turned a little more cautious. While scientific universalism was here to stay, neoliberal skepticism about whether this rationality could be acted upon required a different approach. Rather than imposing universalism on the system by design, the neoliberal west looked to shifted toward simply maintaining order through universal principles.

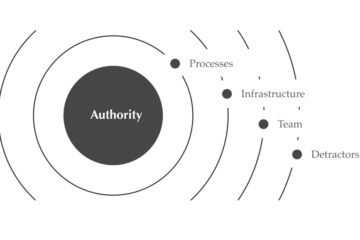

Specifically, if the energy and intelligence of the system came from the nodes, it should be the role of the center to empower (not direct or coerce) these nodes to promote a system that would be healthier and more dynamic as a whole.

In these systems, the way nodes are treated becomes paramount. Distributing information to every node is difficult, so minimal, simple, universal rule-sets are preferred to complex regulatory systems. It is also easy for central systems to abuse individual nodes, so setting restrictions on the central power’s authority is generally focused on.

In the political space, this took the form of emphasizing the rights granted to individuals and the limits on central governments. In economics, it meant stripping away barriers that would slow the natural dynamics between individuals in the system.

In business environments, this meant shifting toward systems that gave lower-level employees more autonomy and basing assessments on producing value through results rather than simply following orders and completing tasks. As we will see in design – this means shifting the focus and definition of “quality” of a design to away from universal measured of aesthetic toward whether it is useful, usable, or desirable to a potential user.

In every case, the emphasis on the system shifts from a focus on the alignment of agents in the system to empowerment. This new universalism changed the nature of bodies that impose will: rather than roll out a plan, they need to simply provide the structures or principles / frameworks that keep natural growth healthy.

In Summary

High modern theory functioned like the classical industrial machine. Because physicist had a mastery over basic Newtonian physics, mechanical engineers could feel relatively confident in the design of their machines. The society-as-machine paradigm is something, however, that Neoliberals cautioned against. To them, society still functioned according to scientific principles, but unlike simple physics, the principles that underlies social functions were too complex for social engineering to be possible. Society was more more akin to studying complexity, systems theory, or cybernetics, wherein a system cannot be designed because there are too many intractable facts at play.

When Hayek and Lippman first started writing about this theory, it was new and relatively unpopular. As the decades progressed, however, and the Mont Pelerin society spun off more think tanks, entered more universities, and began to produce students, these basic assumptions about the nature of the world began to take hold; by the late 20th century, the neoliberal conception of the world was all-but ubiquitous in the English speaking world in both private enterprise and the political sectors.

It was this influence – and this orientation toward the individual (citizen, customer, user…) that shaped the “garden” that late 20th century design practice would grow in.

The Garden

In addition to supplying the philosophical rationale for design to take on a more human-centered approach, the neoliberal era changed the economic landscape as well.

The most important driver of the methods of production is the motivations behind it. Human societies have seen methods of energizing human labor, from honor and glory cultures thousands of years ago, through the pull of monotheistic religion in the past few hundred years, and on to capital which has become a primary driver most recently.

While the flow of capital can take many forms ((later in this essay, we will touch on the way modern China directs capital)), in the US during the late 20th century, the predominant arrangement and flow of capital was driven by neoliberal theories of the open market. The logic of this game was simple: the goal was a higher return on one’s investment, and to achieve it, an organization must create what will be valued by agents in the marketplace. Corporations in the consumer sector operated on the notion that “the customer is always right” and rushed to produce the goods that consumers would buy.

This new focus on the consumer changed the internal composition of corporations. The field of marketing grew in importance and began to shift away from simple communication about product features, to more nuanced understanding and, in many ways, shaping consumer preference.

The conversation about “branding” became more robust as marketers sought to use expressions, emotions, and archetypes((For a wonderful breakdown of archetypical branding, see Margret Mark and Carol S. Pearson’s “The Hero and the Outlaw.”)) to position((For an understanding of how marketing positions products against competition, see Ries and Trout’s book “Positioning”)) products against competitors.

These more nuanced battles on store shelves led to a flurry of psychological research as corporations tried to out-pace one another in any way possible.

Core to all marketing strategy, however, was the neoliberal notion that, at the end of the day, what was “good” would be determined by the consumer. Success would ultimately be determined by what moved best off of consumer shelves, but marketing professionals developed ever more elaborate strategies for understanding these processes before hands through the development of trend-watching organizations, surveys, focus groups, and a host of other methods that would source information from the individuals that would ultimately make the decisions.

The importance of “design” as a practice, of course, varied based on the industry. For general consumables, graphic design and packaging were all that was needed and tremendous focus was paid to keeping design fresh. For more complex products, however, often the product needed to sell itself. As this became more important for hard-goods – and in particular as monetization models started to shift during the push into digital technologies – the industry pulled designers further up the value chain into increasingly more strategic roles.

This shift simultaneously enhanced both the symbolic and pragmatic aspects of design as a more savvy consumer-base – and more competitive corporate focus – ramped up the emphasis on a process that led to a better connection between consumer taste and product form. This shift in corporate focus led to changes in the design process itself, and a more intense focus within that process on human-centeredness.